UofM Magazine

By Trent Shadid

The Hernando de Soto Bridge, with its “M” shape and nighttime illuminations, is among Memphis’ most recognizable structures.

It’s also one of its most vital, as many Memphians and I-40 travelers found out last summer when the bridge was closed for several months after a large crack in a support beam was discovered on May 11. Traffic crossing over the Mississippi River was diverted to the older, narrower I-55 Memphis & Arkansas Bridge without another option within 70 miles of the city.

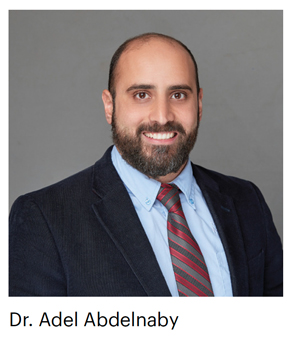

The crack and the lengthy closure came as no surprise to University of Memphis Civil Engineering professor Adel Abdelnaby. A native of Memphis, Egypt, ironically, Abdelnaby has extensive experience inspecting and analyzing bridges throughout the United States and Middle East. That includes the Hernando de Soto Bridge.

Beginning in 2015, Abdelnaby was part of an effort to install seismic sensors on the bridge to measure its ability to withstand possible earthquake activities from the nearby New Madrid Fault Line. The project required the daunting task of walking a catwalk positioned underneath the bridge.

“You can't imagine how much this bridge moves,” Abdelnaby said. “You walk on that

catwalk and a big truck is right on top of you and you feel like you're flying. It

takes your breath away. I’m on my knees holding onto the guardrail.

“You can't imagine how much this bridge moves,” Abdelnaby said. “You walk on that

catwalk and a big truck is right on top of you and you feel like you're flying. It

takes your breath away. I’m on my knees holding onto the guardrail.

“One thing that shows how much this bridge moves is how clean it is. Underneath most bridges, you will see a lot of evidence of birds — feathers, bones, droppings, stuff like that. In this case, there’s nothing. The movement is so significant they avoid it.”

The distinctive shape of the bridge is the culprit of the motion. Designed in the 1960s and completed in 1973, the architects and engineers did not have the technology to predict such issues.

Abdelnaby created a computer simulation to demonstrate the motion of the bridge and highlight hot spots prone to fracture. The design, with cables varying in length and flexibility hanging from the truss and anchored at the deck, creates an uneven stiffness distribution horizontally along the bridge. This causes excessive and localized rotations with hinging at certain locations on the beams. Over time, the repetitive nature of these rotations can result in fatigue cracks through the steel.

According to Abdelnaby, the bridge is twice too long for such a design. The result is consistent and significant wear and tear through hinging of the support beams, particularly near the bridge piers.

“I don't blame the engineers in the 1960s who designed it,” Abdelnaby said. “They didn't have the tools we have today. That was a time when they had to rely on using their hands and their imagination. From an architectural standpoint, it looks great. From an engineering perspective, it is not ideal.”

The excessive movement is also what has made usage of the catwalk a necessity for most work done on the bridge. The catwalk was regularly used for inspections that previously failed to identify the closure-causing crack, which may have existed for half a decade prior to discovery.

A typical inspection of a bridge this size involves a “snooper” truck with a multi-jointed arm and a basket to hold inspectors, providing the capacity to inspect all areas, particularly the structural components on the sides of the bridge not visible from the catwalk. In the case of Hernando de Soto Bridge, instability can make this a potentially unsafe method for workers who are not properly trained to operate the snooper on such a long-span bridge with significant movement at its deck.

“Based on the inspection photos (from the Arkansas Department of Transportation), the inspector was always inspecting the bridge from the catwalk in the center, but this crack was on the outside,” Abdelnaby said. “It’s probably more than 30 feet away and there’s no angle to be able to see it from the catwalk.

“It’s not at all uncommon to inspect a bridge and have certain areas you can’t see or access for various reasons. But when that happens, it must be pointed out in the report so someone can be sent back with the proper equipment. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened in this case.”

An interim fix to the visible fracture was considered in order to quickly reopen traffic on the bridge. Transportation officials instead opted for a multi-phase repair plan to ensure future stability.

“The weight, in this case, will always find the next weakest link,” Abdelnaby said.

“With a fracture in one spot, the weight load is going to be distributed elsewhere

and create distortions that will eventually cause another crack. For this reason,

you have to look at the whole picture rather than the one obvious spot.”

“The weight, in this case, will always find the next weakest link,” Abdelnaby said.

“With a fracture in one spot, the weight load is going to be distributed elsewhere

and create distortions that will eventually cause another crack. For this reason,

you have to look at the whole picture rather than the one obvious spot.”

Preparations were made in an initial phase to safely support workers conducting repairs and inspections. A permanent repair was made at the fractured section while extensive analysis was done to identify other areas displaying signs of fatigue. Locations of concern were repaired and fortified in a final phase before the bridge was reopened.

Though there are flaws in the design that are now obvious, thanks to modern technology and extensive research on bridge fatigue and fracture, the restored bridge is not going anywhere anytime soon.

“The crack causing all of this is repaired in a way that you won’t have future problems in that area,” Abdelnaby said. “They also did the right thing in how they approached fixing all of the bridge. They made safety and future stability top priorities with the best experts in the country involved.”

With an effective repair process completed and more thorough future inspections a certainty, the Hernando de Soto Bridge will remain a signature image of Downtown Memphis for many years to come.