UofM Magazine

Suzanne Onstine’s office sits inside Mitchell Hall, centrally located on the University of Memphis campus. Her work and passion exist on the other side of the world inside Theban Tomb 16 (TT16), an ancient Egyptian burial site near Luxor, Egypt.

Onstine is an associate professor in the Department of History, specializing in Egyptology.

She became interested in ancient Egypt at age 8 after learning how to write her name

in hieroglyphs. As a student at the University of Arizona, she began to see the study

of ancient Egypt not just an area of interest but a potential career. She earned a

master’s and PhD at the University of Toronto while studying Middle Eastern civilizations

with a focus on archaeology.

Onstine is an associate professor in the Department of History, specializing in Egyptology.

She became interested in ancient Egypt at age 8 after learning how to write her name

in hieroglyphs. As a student at the University of Arizona, she began to see the study

of ancient Egypt not just an area of interest but a potential career. She earned a

master’s and PhD at the University of Toronto while studying Middle Eastern civilizations

with a focus on archaeology.

In 2007, Onstine received an American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) fellowship award allowing her studies within TT16 to begin. She has served as the director of the University of Memphis Mission to TT16 ever since. Groups led by her have been studying and working in the tomb since 2008, unearthing hundreds of bones and mummy fragments.

“My whole worldview has really always revolved around thinking about people and their interactions,” Onstine said. “For me, that starts with being really interested in what regular people did in their lives rather than analyzing history the way we typically think about it, which is centered around big battles and well-known elites.

“We so often read about this one great person who did that one great thing without thinking about the thousands of people who made it happen. The success of the general who won the battle was fully reliant on the soldiers that carried out his orders. What was life like for those soldiers? Or what about the women back home who took care of the farm or business? I am especially interested in uncovering the stories of those women, who for so long have really not been given credit in historical records.”

INSIDE TT16

Onstine’s 13 years of work at TT16 has produced glimpses into the lives of those everyday

ancient Egyptians history has regularly neglected.

Onstine’s 13 years of work at TT16 has produced glimpses into the lives of those everyday

ancient Egyptians history has regularly neglected.

The tomb was originally built for Panehsy, a priest in the cult of Amunhotep I, and his wife Tarenu. They lived during the reign of Ramesses II, a statue of whom stands at an entrance to the UofM campus on Central Avenue.

But TT16 has long been a resting place for far more than Panehsy and Tarenu. During the archaeology phase of examining TT16, Onstine and her team discovered the tomb contained an estimated 200 people who had been laid to rest there during the 1,000-year period of the first millennium BC.

“That was something I didn't really expect,” Onstine said. “A tomb is built for one family or one person. While it’s not uncommon for people to reuse these monuments throughout history for additional burials, discovering close to 200 individuals in a tomb is significant.

“Those bodies are individual lives that we can investigate, even without knowing their

names or anything fancy about them. The human body records all kinds of really interesting

details about people’s lives.”

“Those bodies are individual lives that we can investigate, even without knowing their

names or anything fancy about them. The human body records all kinds of really interesting

details about people’s lives.”

These remains may reveal a cause of death, if a person dealt with arthritis from the work they performed, or any conditions they may have had at various stages in their life. Hair analysis can give a more detailed look at their last few years by preserving a snapshot of chemical makeup. Stable isotope testing allows for even further examination, such as whether these ancient Egyptians drank from the same water source all their life or if, and how regularly, they moved around.

“The body, as a sort of historical document, has really opened up a lot of questions I can ask about the Egyptian population in a more general way,” Onstine said. “We really can think about so many different things that a text might not tell us. I have an anthropology background so I know it’s important to look at human remains, but the level of specificity has really been very eye-opening.”

AS SEEN ON NAT GEO

If you are a fan of informational films about ancient Egypt, there’s a good chance you have seen Onstine on your TV screen.

She appeared in two episodes of the 2019 National Geographic documentary series Lost Treasures of Egypt. Other television appearances include the documentary series Tutankhamun with Dan Snow (2019) and the documentary movie Egypt’s Ten Greatest Discoveries (2008).

She appeared in two episodes of the 2019 National Geographic documentary series Lost Treasures of Egypt. Other television appearances include the documentary series Tutankhamun with Dan Snow (2019) and the documentary movie Egypt’s Ten Greatest Discoveries (2008).

“For (Lost Treasures of Egypt), they spent four days with us in the tomb, basically filming various aspects of the work and doing the on-camera interviews,” Onstine said. “Off camera, we did a lot of talking about what might be interesting to film. They asked me what I might have in the tomb that answers a particular question. In all cases, they come in with a very specific idea of what they want their show to highlight and we work together to create that.”

Onstine has been regularly contacted by producers for several other TV specials that either never made it to full production or were not the right fit for her professionally. The shows have helped her connect with all kinds of different people, from fans of ancient Egypt to potential collaborators to admirers of her work.

In addition to the on-screen appearances, Onstine has had three books published or accepted for publication, contributed to several journal articles and presented at renowned conferences. Her career achievements make her easy to identify as an expert in her field.

“Even without the TV shows, Egyptologists generally get a lot of questions from the public because people love ancient Egypt,” Onstine said. “They do a Google search for experts, see your info and send random questions all the time. I've gotten requests for tattoos. People want to get certain tattoos in hieroglyphs, so they contact an Egyptologist and say, ‘Can you write this in hieroglyphs for me?’

“Beyond that, I get very kind messages from people who are really interested in particular with the National Geographic material, because it was so focused on human remains and the story of women.”

PRESERVING ANCIENT EGYPT

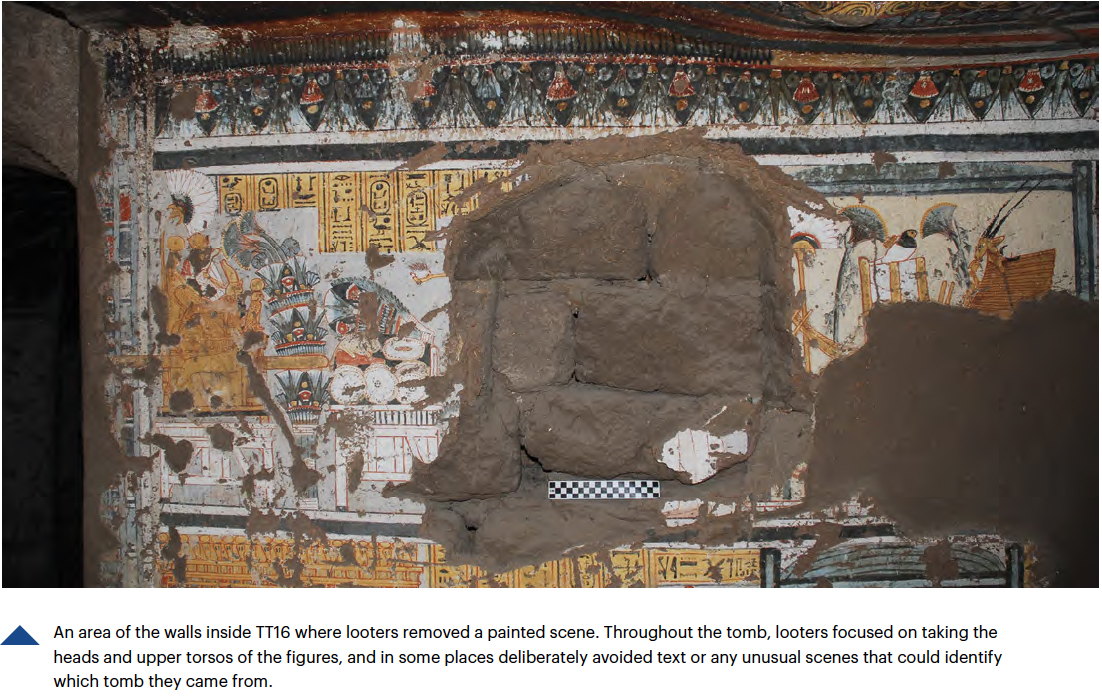

At the core of Onstine’s work is a strong desire to stress the importance of protecting mummified remains and artifacts from looters. She has seen firsthand the havoc that has been caused by thieves raiding tombs in hopes of making a profit in the art market.

In TT16, there are no complete individual bodies. There are many mummified body parts that have been unwrapped and torn apart in the looting process. This has made it impossible to know for certain how many people were buried in TT16 or discover any extensive genealogical connections among them.

“The state of the tomb that I work in, the devastation of those bodies that have been ripped apart, was specifically to get and sell the very tiny scarab amulets that we're wrapped inside those bodies,” Onstine said. “Imagine how much more information we could get from those individuals if not for the looting. We could maybe know their names, know their family status and rebuild their history if they had not been thoroughly torn apart in search of little things to sell.”

The discussion around looting has also put archaeologists in a position of having to defend their own work at times. There are dissenting voices who see looters and archaeologists as one and the same simply because both are digging up remains inside a tomb.

For Onstine, the difference is very clear. Her purpose is to preserve and honor the people of the past by paying attention to the details and treating them with respect. She is focused on putting together a history of human lives and building knowledge of their experiences in order to educate people about the past rather than doing what she does for monetary gain or entertainment.

“The desire for people to own one tiny artifact led to the destruction of entire family burials,” Onstine said. “The impact of that is usually unseen to the people who are buying those things. So, I feel like I have a responsibility to educate people on this particular thing. I always like to emphasize that buying these antiquities, not only is it illegal, but it encourages the looting of ancient sites in Egypt and all over the world.

“It’s the most important thing I can stress to anyone with interest in Egyptology or preserving history in general.”

|

|

ANCIENT EGYPT AT THE UofM

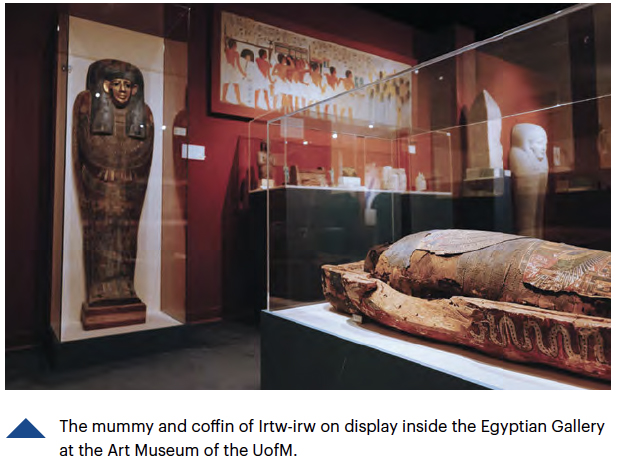

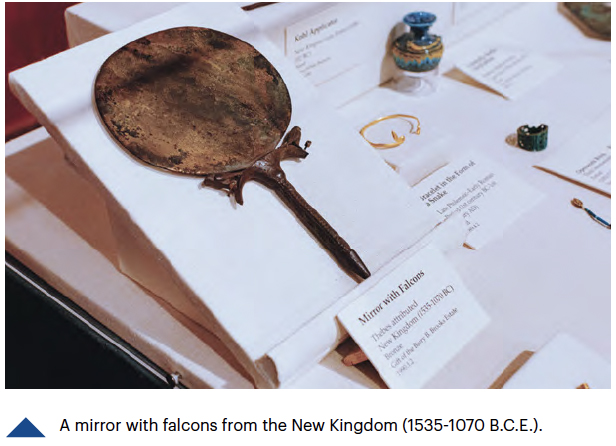

Memphians do not have to travel far to get an up-close look at ancient Egyptian artifacts. Approximately 250 are on permanent display on the UofM campus. Ranging in date from 3800 B.C.E. to 700 C.E., the items are housed inside the Egyptian Gallery of the University’s Art Museum.

The oldest item within the gallery is a flint hand ax from the Acheulean Period (100,000 B.C.E.). The gallery also includes the coffin and mummy of Irtw-irw from the Ptolemaic Period (304-30 B.C.E.), a 4,000-year-old loaf of bread, musical instruments, religious items and much more.

In total, the UofM has a collection of 1,400 ancient Egyptian objects spanning the entire range of ancient Egyptian history and prehistory. The collection began in 1975 with 44 items obtained for the University from the Museum of Fine Art in Boston through the generosity of prominent Memphis businessman E.H. Little. Since that time, the collection has consistently grown to its present size mostly through the generosity of private donors.

As part of the Master’s Program in Egyptology, students are allowed the opportunity to choose an item from the collection as the subject of their thesis. In addition, scholars from all over the world regularly contact the UofM’s Institute of Egyptian Art & Archaeology regarding objects in the collection.

For more information on the exhibit, visit memphis.edu/egypt/exhibit.