Benjamin Lawson Hooks Papers

Benjamin Hooks, His Life in the Church

by William C. Love

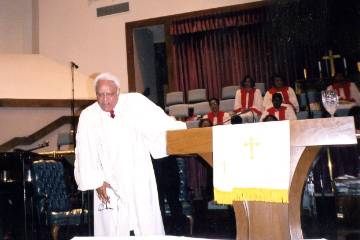

The Reverend Benjamin Hooks and His Life in the Church

“For as long as I can remember, the church has been an integral part of my life.”

So opened Dr. Hooks in a chapter of his memoir entitled “My Life and the Church.”

While Dr. Hooks is primarily remembered for his accomplishments as a lawyer, judge,

and NAACP executive, Dr. Hooks devoted a substantial part of his life to the church,

as both a layman and a minister.

“For as long as I can remember, the church has been an integral part of my life.”

So opened Dr. Hooks in a chapter of his memoir entitled “My Life and the Church.”

While Dr. Hooks is primarily remembered for his accomplishments as a lawyer, judge,

and NAACP executive, Dr. Hooks devoted a substantial part of his life to the church,

as both a layman and a minister.

Hooks recalled that some of the social norms of his churches made him uncomfortable from an early age. He never believed that public confession of one’s salvation was central to the Christian life and felt uncomfortable in the revival seasons of the church. Rather, Hooks believed that his own experience of a gradual but “growing awareness that God exists, that Jesus Christ is His only begotten son, and acceptance of him in my life as Lord” was as acceptable a path to the Christian life as a lightning bolt moment of salvation. What Hooks remembered enjoying most about church were the liturgical aspects of worship, namely hymn singing, deep-water baptisms, and the Decalogue chant very common in the AME tradition.

Dr. Hooks’ career as a pastor began in May of 1955 when he announced to the congregation of First Baptist Church that he felt called to preach. Even though Hooks had no formal seminary education, he was licensed to be a Baptist minister after an endorsement from his friend Reverend Nabrit and a vote of confidence from the local congregation. A few months later, Hooks became pastor of Middle Baptist Church and in 1963 was offered the pastorate of Mt. Moriah Church in Detroit, Michigan. Initially, Hooks felt uneasy about leaving Memphis and declined the offer, offering to preach twice a month on an interim basis. After much discussion with both churches, a decision was made for Hooks to be the official pastor of both Mt. Moriah and Middle Baptist, alternating between Memphis and Detroit to minister both churches. While his duties as FCC commissioner and NAACP Executive Director compelled him to leave full time ministry, he maintained close connections to both churches, preaching to both relatively often for no pay. Hooks continued to be a co-pastor or pastor emeritus of both churches until his death in 2010.

The Hooks Papers have few manuscripts available on Hooks’ tenure as a pastor. There

are only five boxes that pertain to his time as a pastor and they mostly contain printed

material which include church bulletins and church administrative materials such as

budget outlines and board minutes. A recent addition to the Hooks collection contains

a box of note cards, in Hooks’ writing, that he probably wrote in preparation for

either sermons or general Bible study. However, the notes are mostly thought fragments

pertaining to Bible passages. No manuscripts of Hooks’ sermons survive and most likely,

Hooks preached his sermons using only loose outlines.

The Hooks Papers have few manuscripts available on Hooks’ tenure as a pastor. There

are only five boxes that pertain to his time as a pastor and they mostly contain printed

material which include church bulletins and church administrative materials such as

budget outlines and board minutes. A recent addition to the Hooks collection contains

a box of note cards, in Hooks’ writing, that he probably wrote in preparation for

either sermons or general Bible study. However, the notes are mostly thought fragments

pertaining to Bible passages. No manuscripts of Hooks’ sermons survive and most likely,

Hooks preached his sermons using only loose outlines.The best source of Hooks’ preaching is far and away the audiocassette portion of the Hooks collection. The original collection contains close to two dozen recordings of Hooks’ sermons, primarily in the 1980s but a recent addition from his daughter, Patricia Hooks, contains close to 20 new recordings of Hooks’ sermons, many of which date from after his retirement from the NAACP. All of the sermons are now digitized. They are typically between 20 and 30 minutes in length and were usually preached either at Mt. Moriah Church in Detroit or Middle Baptist Church in Memphis, Tennessee.

Hooks’ sermonic style echoed the call and response tradition of many Black Churches. Hooks preached in such a way that the rhythm and crescendos of the sermon were as important as the content. The rhythm invited the congregation to participate in the preaching, and thus were truly a communal activity. In the recordings, one can hear both Hooks’ preaching and the responses of the congregation typically affirming the mood, tone, and substance of the sermons.

From a thematic standpoint, Hooks’ sermons often repeated familiar territory, i.e.

a harsh, often chastising tone concerning the state of the Black family and the Black

church. In several of his sermons, one hears Hooks quoting Charles Dickens’ A Tale

of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

From a thematic standpoint, Hooks’ sermons often repeated familiar territory, i.e.

a harsh, often chastising tone concerning the state of the Black family and the Black

church. In several of his sermons, one hears Hooks quoting Charles Dickens’ A Tale

of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”On the one hand, Hooks was clear that Black Americans had made substantial progress in the last two decades, thanks to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Black Americans had cumulatively earned enough wealth that if they consolidated it and moved it in a single direction, they would have enough influence to bring even the biggest corporation to its knees. Black Americans were now mayors, police officers, judges, and business owners in numbers unprecedented in American history.

On the other hand, Hooks believed that the Black community was in a greater crisis now than any other time in history. He often made pointed jokes of Black Americans “tithing to the local liquor store” and stark remarks about the level of violence prevalent in many Black neighborhoods, noting that the number of Black men murdered by other Black men was far greater than the number of Black men lynched in the early twentieth-century South. The remedy for this problem was not government intervention (though Hooks as NAACP director tirelessly advocated for the prolonging of targeted programs) but rather a revival within the Black community, centered on the church and the family.

If one compares the substance of Hooks’ sermons to his speeches given on behalf of

the NAACP, one might conclude that Hooks often spoke from both sides of his mouth.

While Hooks advocated tirelessly on behalf of the Black community and fought to keep

targeted government programs in place as director of the NAACP, as a preacher Hooks

displayed little patience for members of the Black community that were lazy. In one

of his last sermons, he recalled the luxuries available to even the poorest among

the Black community, contrasting it to his own mother who ate her breakfast from the

scraps of her young children.

If one compares the substance of Hooks’ sermons to his speeches given on behalf of

the NAACP, one might conclude that Hooks often spoke from both sides of his mouth.

While Hooks advocated tirelessly on behalf of the Black community and fought to keep

targeted government programs in place as director of the NAACP, as a preacher Hooks

displayed little patience for members of the Black community that were lazy. In one

of his last sermons, he recalled the luxuries available to even the poorest among

the Black community, contrasting it to his own mother who ate her breakfast from the

scraps of her young children.However, it was not hypocrisy that drove Hooks to these statements but rather a common trope within Black preaching: the historical struggle of the American Black community contained its greatest strength. It was through struggle and perseverance that the Black community had attained so much of its best features, both for itself and America-at large. The Black community needed to embrace its struggles, rather than resting on simple material advances or pride in its own customs and achievements. Hooks continued preaching this theme well into the 2000s and always believing that the destiny of the Black community was intrinsically tied to the values and traditions of the Christian faith. Hooks and the FCC >