Welcome to the Great Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Karnak

|

In antiquity, Karnak was the largest religious sanctuary in Egypt's imperial capital of Thebes (modern Luxor) and was home to the god Amun-Re, king of the Egyptian pantheon. For over 2000 years, successive pharaohs rebuilt and expanded the temples of Karnak, making it the largest complex of religious monuments from the ancient world.

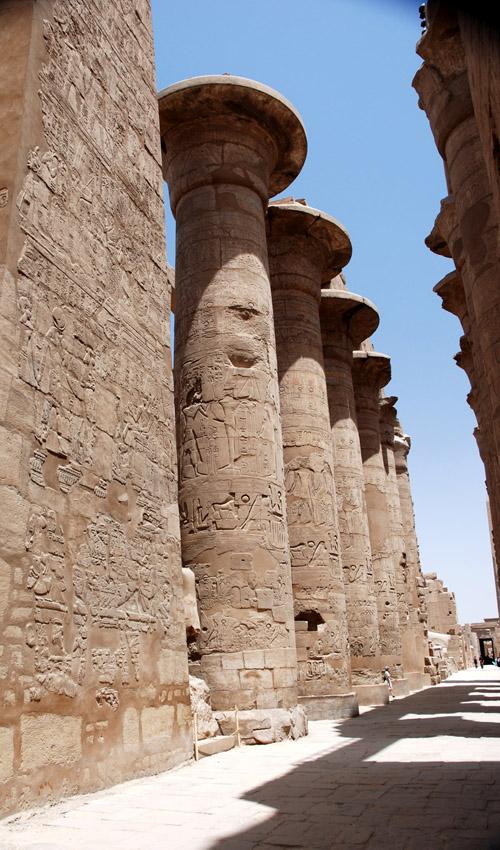

At the heart of Karnak, the Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh Sety I (reigned ca. 1291-1279 BCE) erected his Great Hypostyle Hall, a colossal forest of 134 giant sandstone columns supporting a high clerestory roof and enclosed by massive walls that after 3300 years remain substantially intact today. The Great Hall is vast. It covers an acre of land, and its great columns soar to heights of 20 meters. Not only does the scale and completeness of this monument remain a rarity among ancient Egyptian temples, but it is also the largest and most elaborately decorated of all such buildings in Egypt. Visitors often remark on the bewildering array of inscriptions covering every surface: the walls, columns, and even the roof! The patchwork of artistic styles and different royal names seen in these inscriptions and relief sculptures reflect the different stages at which they were carved over the centuries. Successive pharaohs, Roman emperors, high priests and common Egyptians added to its wealth of inscriptions and relief decoration, made architectural alterations and restorations, and even left pious graffiti on its walls.

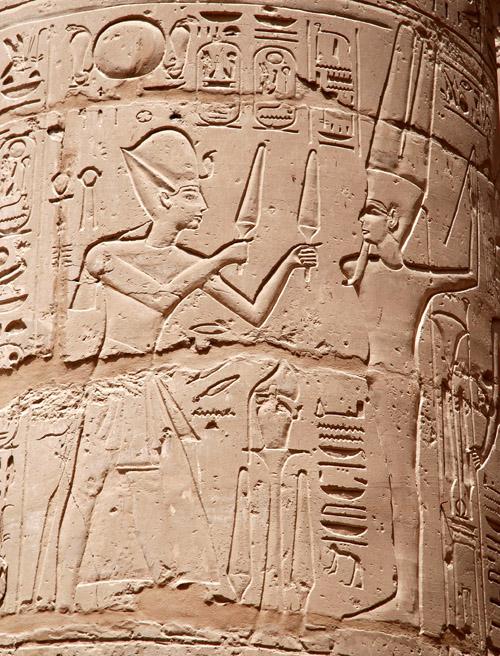

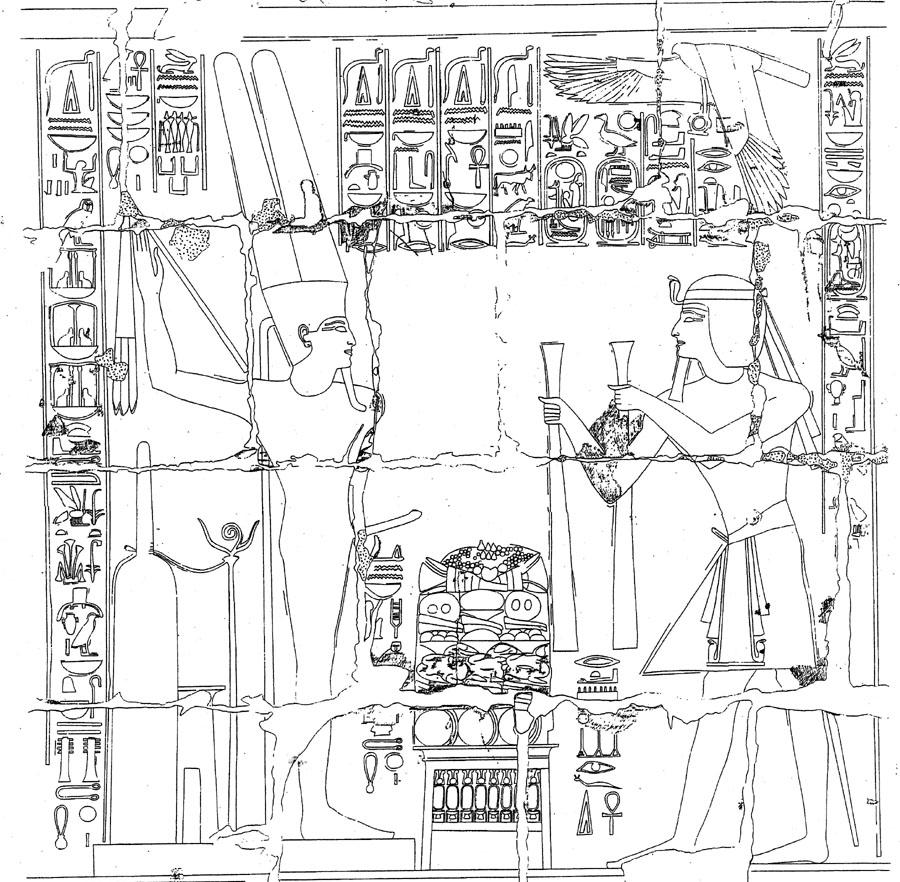

Sety I’s craftsmen embellished the walls and columns in the north half of the building with exquisite bas relief sculptures of the highest quality before the king’s death. Sety’s successor, the celebrated Pharaoh Ramesses II (reigned ca. 1279-1213 BCE), commanded his artisans to carve the walls and columns in its southern wing mostly in sunk relief in various phases over the course of his long reign.

Later rulers like Pharaoh Ramesses IV (ruled ca. 1151-1145 BCE) and the High Priest of Amun Herihor (ruled ca. 1080-1072 BCE), seeking to associate themselves with the Hall and its illustrious builders, inserted further decoration into spaces previously left blank or even superimposed over earlier inscriptions on the columns. Thereafter, the Great Hypostyle Hall remained in use for seventeen centuries, down to the end of paganism in Egypt during the fourth century of our era.

Constituting a monumental encyclopedia of Egyptian civilization, the Great Hypostyle Hall's reliefs and inscriptions attest to the richness and vitality of Egyptian civilization at the height of its imperial power during the last two centuries of the Egyptian New Kingdom (ca. 1300-1100 BCE). They document Egyptian religious beliefs, culture, political history, and foreign relations.

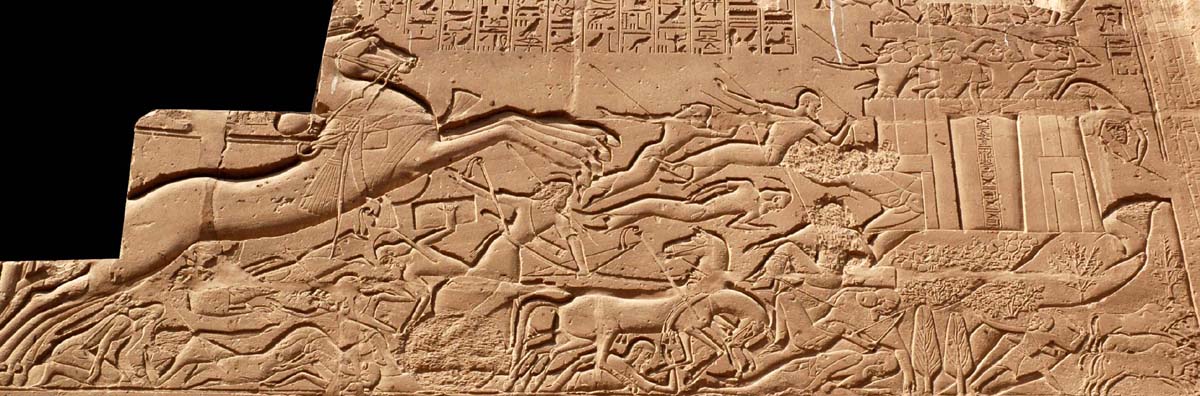

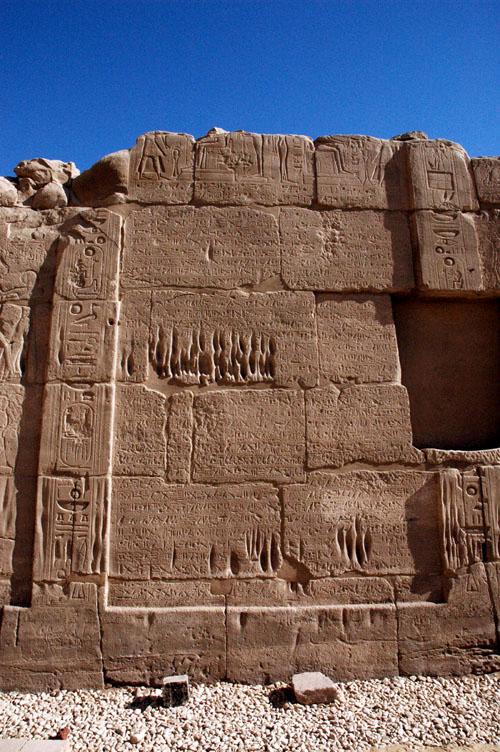

As Sety I and Ramesses II were constructing and inscribing the Great Hypostyle Hall, Egypt and the Hittite Empire—the two military superpowers of the 13th Century BCE—were locked in a bitter, seven decades-long war for control of ancient Syria. Both kings left panoramic war scenes on the exterior walls of the Hypostyle Hall that commemorate the last stages of this conflict. Hostilities ended in the 21st year of Ramesses II’s reign (ca. 1258 BCE) when he concluded the earliest known international peace treaty in human history with the Hittite Empire. Ramesses marked the event with a hieroglyphic copy of his treaty carved in stone on a wall just beyond the southern gate of the Hypostyle Hall.

Karnak has long been one of the major sites for the millions of tourists who visit southern Egypt. Thousands pass through the Great Hypostyle Hall and the rest of Karnak on a daily basis, taking countless photos of its wonders. Yet even after two centuries of archaeological excavation and scientific study by Egyptian, French, and American Egyptologists, most of the Karnak complex remains scientifically undocumented today. As one of our Egyptian colleagues puts it, Karnak is an archaeological ocean, and we have barely dipped below its surface.

This unfathomed sea of antiquities is most profound in the Great Hypostyle Hall, a majestic structure that overwhelms the viewer with a vast array of wall carvings and hieroglyphic inscriptions and whose sheer scale and complexity has largely defied scholarly efforts to record and study it. While this priceless trove of irreplaceable inscriptions has much to teach us about Ancient Egypt, Egyptologists have only ever scientifically recorded a fraction of them, their true significance being neither well-understood nor fully appreciated. Alarmingly, a combination of environmental and human-made factors have caused this vast repository of inscriptions to decay and even threatens to destroy the building altogether. Inscriptions and relief carvings have long suffered from infiltration of ground water, as mineral salts in the stone draw moisture upwards by capillary action, and this, in turn, forces the salts to crystallize on or beneath the surface, destroying the relief.

The Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project

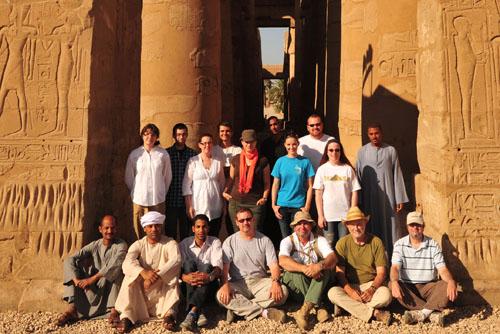

The Karnak Great Hypostyle Hall Project is a joint endeavor of the University of Memphis, in Memphis, Tennessee (U.S.A.), and the Université de Québec à Montréal (Canada). We work in cooperation with Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities and the Centre Franco-égyptien d’études des temples de Karnak (France). Our project has three closely related aims:

|