Tent City: Stories of Civil Rights in Fayette County, Tennessee

Fayette County Activists

Stories of Fayette County, Tennessee

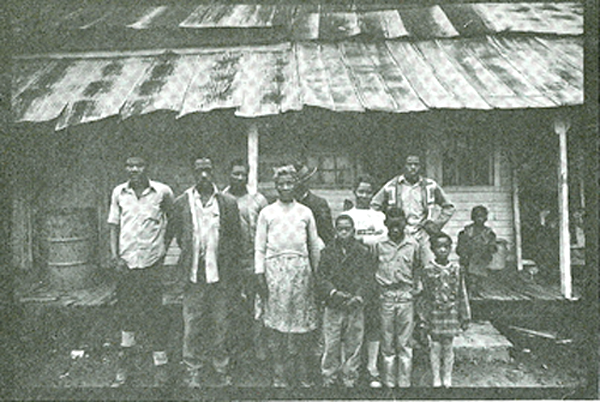

Gertrude Beasley

Photo (left): Beasley (center) and her family standing before their home. Source:

Michael Abramson.

Photo (right) Beasley. Source Tim Hall.

Gertude Beasley showed compassion and courage in permitting a second Tent City to be erected on her farm for the black sharecropping families who had been evicted by white landowners because they registered to vote. Despite having limited resources of her own, Beasley's generosity provided evicted Black families with a place to live in a county where many families were unjustly denied shelter.

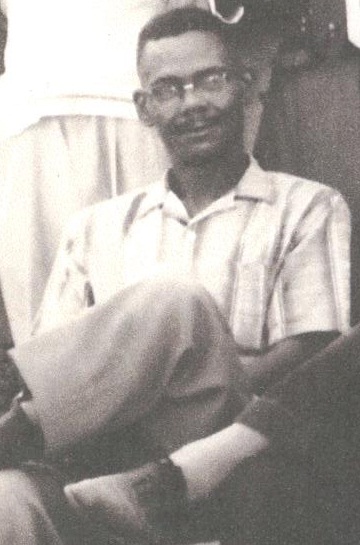

E.V. Braswell

|

|---|

| Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust. |

E.V. Braswell was a League board member and the League's leader for Fayette County's electoral District 9 ( The district numbers in this program refer to former district numbers, not to current designations. The league selected a leader from each district to serve as a liaison between the League and the community).

Braswell, among other things, educated people in his district about voter registration,

the election of Black candidates, employment, housing, and other opportunities. Braswell

played a crucial role in locating and raising funds to purchase the land used for

the Community Center site and to pay for the building itself.

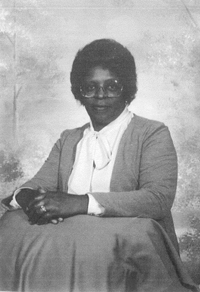

Norma Cox

|

|---|

|

Source: McFerren/ Family Collection |

In the 1970s, after having previously taught at all-black schools as an elementary school teacher, Norma Cox was assigned to Somerville Elementary. At that time, few black students attended Somerville Elementary because it had been a historically white school prior to integration. At Somerville Elementary, in an attempt to punish Cox, her colleagues and the principal isolated her. The principal not only assigned her to teach physical education, a class she had not previously taught, but he also forced to teach them in the harshest of weather conditions.

Further, she was assigned a restroom in the school as her office. Cox used this restroom as her office for approximately three years. Finally, after tiring of the discrimination against her, Cox contacted the League, who, in turn, solicited the assistance of Attorney Avon N. Williams to address Cox's working conditions. Through court action, Cox was finally transferred to another school and was assigned a class to whom she could teach subjects that aligned with her education and interests.

Venetta Gray

|

|---|

|

Source: Gray/Family Collection. |

Venetta Gray and her husband, Houston Gray, were parents who joined in the lawsuit to desegregate Fayette County schools. Venetta Gray was a loyal member of the League.

She encouraged people to register to vote and informed community members about education, employment, housing loans, and other issues that would have a positive impact on the quality of black life.

William Hayslett

In 1966, Hayslett was one of the six black county commissioners elected to the Fayette

County Quarterly Court. Previous to this election, blacks had not held elected positions

in Fayette County. He served as a commissioner for 34 years.

In 1966, Hayslett was one of the six black county commissioners elected to the Fayette

County Quarterly Court. Previous to this election, blacks had not held elected positions

in Fayette County. He served as a commissioner for 34 years.

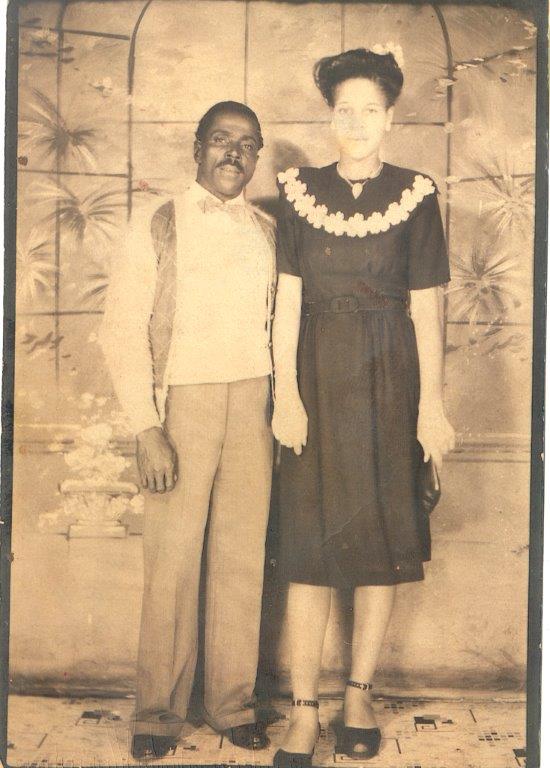

Roosevelt and Marie Herron

Roosevelt Herron served many years as a League board member, and he and Marie Herron

took a leading role in raising money to pay for the Community Center and other League

expenses. After John McFerren, Jr. was dismissed from school for allegedly hitting

a white teacher, Roosevelt Herron investigated the facts surrounding this incident

and found that John had not hit the teacher but instead, a young girl had accidentally

bumped him into the white teacher. Herron later convinced the child's parent to permit

the child to testify to these facts in federal court. An order from Federal District

Judge, Robert McRae, led to John McFerren, Jr.'s reinstatement in elementary school.

Roosevelt Herron served many years as a League board member, and he and Marie Herron

took a leading role in raising money to pay for the Community Center and other League

expenses. After John McFerren, Jr. was dismissed from school for allegedly hitting

a white teacher, Roosevelt Herron investigated the facts surrounding this incident

and found that John had not hit the teacher but instead, a young girl had accidentally

bumped him into the white teacher. Herron later convinced the child's parent to permit

the child to testify to these facts in federal court. An order from Federal District

Judge, Robert McRae, led to John McFerren, Jr.'s reinstatement in elementary school.

Maggie Mae Horton

|

|---|

|

Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust. Tim Hall/ Personal Collection |

During the 1960s, Maggie Horton was an aggressive activist who worked with the League

to create solidarity among blacks in her voting district, District 10, and in other communities throughout the county. Horton spent countless hours speaking

with and arranging transportation for blacks to register and vote. Charismatic and

energetic, Horton personally supported and encouraged others to participate in the

League's mass demonstration marches and other civil rights efforts. Horton's district

was considered one of the League's best organized districts.

Maggie Mae Horton Discusses Her Experiences in Fayette County

2002 Documentary Project on Fayette County, TN: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

Harpman and Minnie Jameson

|

|---|

|

Source: Jameson/family collection. |

Starting from 1959, Harpman and Minnie Jameson were at the center of the dynamic leadership of the League. Harpman Jameson, a World War II veteran inducted into service on November 8, 1943, was one of the first blacks in 1959 to register to vote in Fayette County. Both Jamesons served approximately 40 years on the League's board of directors.

Harpman's Contributions

Mr. Jameson served over 40 years as the League Treasurer. From 1959 through the late 1970s, he actively worked to encourage people to register to vote. From 1959 and into the millennium, Jameson worked in practically every election at the local, state, and national levels.

Minnie's Contributions

From approximately 1959 to 2001, Minnie Jameson served as League Secretary. She was the primary publisher of the newsletter, "The League's Link." During the 1960s and on behalf of the Board of Directors, she and her sister, Viola McFerren, wrote much of the correspondence between the League and other people and/or organizations, ranging from offers of assistance or guidance for the League's efforts to criticisms.

Minnie Jameson's correspondence, flyers and other documents comprise much of the material donated to Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries. Further, correspondence drafted by both Minnie Jameson and Viola McFerren can be found in other library collections, including the collection of Virgie Hortenstine on Fayette County, and held by Wilmington College in Cincinnati, Ohio. In addition to their work for the League, Minnie Jameson and Viola McFerren provided emotional support to each other, their families and others throughout the turbulent 60s when League members feared serious injury or death for their activism. Ms. Jameson's compassion and love for her extended family, and her abiding love for the League, encouraged Daphene McFerren, Robert Hamburger, and others to preserve the League's history so that the Movement would not be forgotten.

Geraldine Johnson

|

|---|

|

Source: Tim Hall/Personal collection. Johnson on left. |

In 1966, Ms. Johnson was one of six African American county commissioners elected to the Fayette County Quarterly court. Prior to this election, no African Americans had held elected positions in Fayette County.

Mandy Junkins

Junkins is the sister of Mary B. Williams. Like the Williams family, Junkins, also

a sharecropper in 1959, registered to vote and was forced to move her family to Towles'

farm after the white landowner evicted her family for having registered to vote.

Junkins is the sister of Mary B. Williams. Like the Williams family, Junkins, also

a sharecropper in 1959, registered to vote and was forced to move her family to Towles'

farm after the white landowner evicted her family for having registered to vote.

Albert Sylvester and Nora Lewis

|

|---|

| Source: Lewis/ Family Collection |

During the 1960s, many civil rights workers from across the country came to Fayette County to work with the League and others in their civil rights efforts. These workers found it extremely difficult to drive over the unpaved muddy roads in the African American community and other rural areas and frequently got their cars became stuck in the mud.

In 1965, Albert Lewis, a local farmer, drove his tractor to rescue a civil rights worker's car from the mud. While attempting to pull the car out of the mud, his tractor turned over on him and killed him.

Despite this great personal loss, his wife, Nora Lewis, continued to support the League's

efforts to integrate Fayette County Schools by enrolling her children in previously

all-white schools.

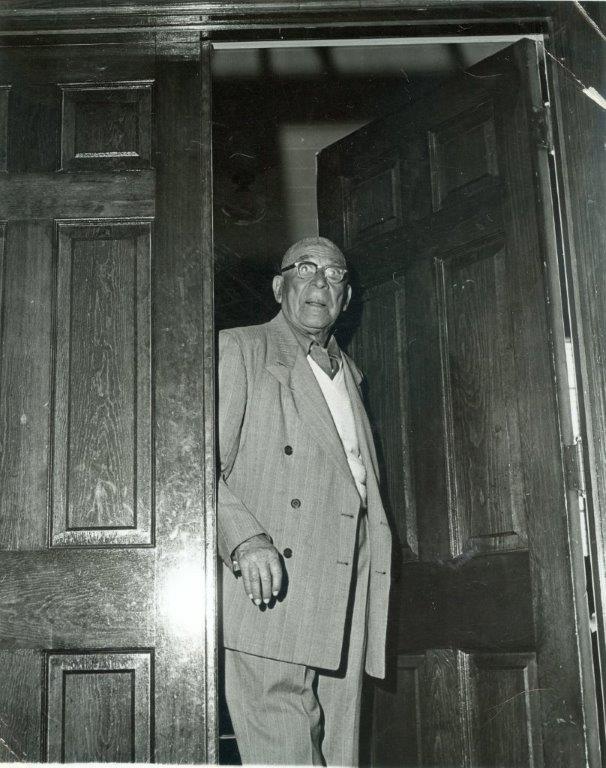

John Lewis

|

|---|

| Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust. |

From the inception of the Movement in 1959, many of the strongest supporters of the Movement leaders' efforts were elderly African Americans who had lived a lifetime under segregationist practices. In October 1961, Lewis, at the age of 85, voted for the first time in the Fayette County Democratic primary.

Shortly after the numerous evictions of Black sharecroppers from white farms, Lewis

encouraged John McFerren to start a business to supply food and gas to the African

American community after he saw that whites refused to sell to Blacks who had registered

to vote goods or provide services. McFerren relied on Lewis for his encouragement

and counsel, and had profound respect for Lewis's wisdom, courage, conviction and

love of people.

Houston Malone

Source: Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust |

In 1960, after registering to vote, Houston Malone, along with his wife and children, were forced to move from the farm they were sharecropping. Malone often told League members that he "walked the road day and night until the soles of my shoes were bare looking for a place to live." This eviction spurred Malone into action. He served as the leader for District 7 for the League. Malone worked long and hard throughout his community to encourage people to register to vote and to educate his community about opportunities that would improve the quality of their lives. Houston served for over 30 years as the League's treasurer. The League board of directors and members loved Malone for his kindness, generosity of spirit and his dedication to the service of others.

Etta B. Mason

Mason, the daughter of Gertrude Beasley, was evicted from a white landowner's farm

after registering to vote. She then moved into a tent on her mother's farm. In January

1961, Ms. Mason gave birth to a son, Cleo. Tent City residents and Movement leaders

worried that the baby might die from the weather, which was extremely cold that year.

While the baby survived, Mason's family pet dog froze to death the night of Cleo's

birth.

Mason, the daughter of Gertrude Beasley, was evicted from a white landowner's farm

after registering to vote. She then moved into a tent on her mother's farm. In January

1961, Ms. Mason gave birth to a son, Cleo. Tent City residents and Movement leaders

worried that the baby might die from the weather, which was extremely cold that year.

While the baby survived, Mason's family pet dog froze to death the night of Cleo's

birth.

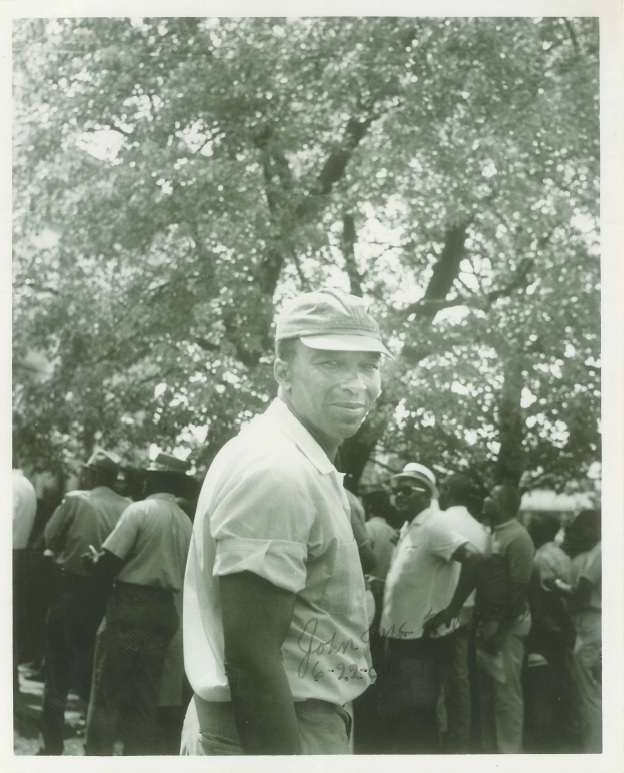

John McFerren

Source: McFerren/Family Collection |

John McFerren, a World War II veteran, was inducted into the military on November 9, 1943 and served in Europe. During his service in the army, he met Staff Sergeant J.F. Estes, at an army camp in Illinois. They would later cross paths again in 1957 at Burton Dodson's trial, where Estes represented Dodson on the criminal charges of allegedly killing a white deputy sheriff. Estes encouraged McFerren and Harpman Jameson to empower their community by encouraging blacks to register to vote. In the summer of 1959, Mcferren and Jameson started a voter registration drive among African Americans in Fayette County that forever changed the relationships between Black and whites in that county.

Estates, working with Mcferren and the African American community, created a civic organization, the Fayette County Welfare League [the name was later changed in 1961 to the Original Fayette County Welfare League inc.], to help advance the welfare of African Americans. At its' inception, the League's primary objective was to register African Americans to vote. McFerren, at great cost to himself and his family, led the community to fight for their constitutional rights to be treated as equal citizens of the United States.

Viola McFerren

Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust |

In 1947, Viola McFerren moved to Fayette County to attend W.P. Ware High School because Benton County, Mississippi did not provide schooling for Blacks beyond 8th grade. While attending high school in Fayette County, she met and married John McFerren. From almost the inception of the Movement, she worked with the Original Fayette County Civic and Welfare League to fight for civil rights. Throughout the years, she worked tirelessly to improve the welfare of the entire Fayette County community.

During the early1960s, McFerren accepted speaking invitations from around the country where she spoke about the plight of black families who had registered to vote in Fayette County. Her efforts to publicize the story of Tent City helped raise much-needed funds needed by evicted families for the League's community outreach. As a League representative, she worked closely with Attorney Avon N. Williams to desegregate the Fayette County schools.

In 1966, she was appointed by President Lyndon Baines Johnson to serve on the National Community Representative Advisory Counsel to the National Office of Economic Opportunity (the Anti-Poverty Program). Her work on that committee led her to spearhead the creation the Anti-Poverty Program in Fayette County and to later serve on the board of directors of the League. Additionally, she played a pivotal role in the creation of the Head Start program in Fayette County.

Descriptions of the Movement and John and Viola McFerren's civil rights activities can be found in Notable Black Women of Achievement (Volume 2) (2003); Blacks in Tennessee, by Lester Lamon (1981); Our Portion of Hell, by Robert Hamburger (1973); Step by Step: Evolution and Operation of the Cornell Students' Civil-Rights Project in Tennessee, by Fayette County Project Volunteers (1964).

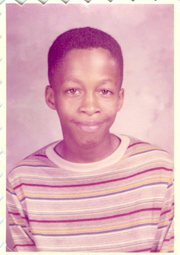

John McFerren Jr.

Source: McFerren/ Family Collection |

In July 1965, the Original and Fayette County Civic and Welfare League authorized Attorney Avon Williams, Jr., an African American attorney whose work was supported by the NAACP, to file a federal school desegregation suit against Fayette County in the United States District Court for the West District.

While McFerren, Jr. was only 6 years old at the time, he was the lead plaintiff in that action. Shortly thereafter, McFerren, Jr., along with others, began integrating schools. McFerren, Jr. was the target of sustained taunts and fights initiated by white classmates and anger from white teachers who disapproved of school integration and especially disliked McFerren, Jr. because of his family's role in the Movement.

Although McFerren, Jr. was only a child, he endured great hardship in being the named plaintiff of a lawsuit to integrate schools and being among the first to integrate previously all-white schools.

John McFerren Jr. Discusses Desegregation

2002 Documentary Project on Fayette County, TN: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

Square Mormon

Source: Photo on left of Square Mormon attending 2006 Conference at The University of Memphis, Benjamin L. Hooks Institute of Social Change. Photo on right of Square Mormon, courtesy of Tim Hall.

During the 1960s, Square Mormon was an aggressive activist who worked with the League to foster solidarity among blacks in his voting district, District 10, and other communities throughout the county. Square and his wife, Wilola Horton, joined early in the League's efforts to educate the black community about the importance of registering to vote. They worked relentlessly, spending countless hours speaking with and arranging transportation for blacks to register and to vote.

Mormon was also a founding member of the Rossville Health Care Clinic whose primary mission was to provide health care to poor and underserved communities in Fayette County. This clinic has become a Fayette County institution in operation to serve underserved and underinsured people in the county.

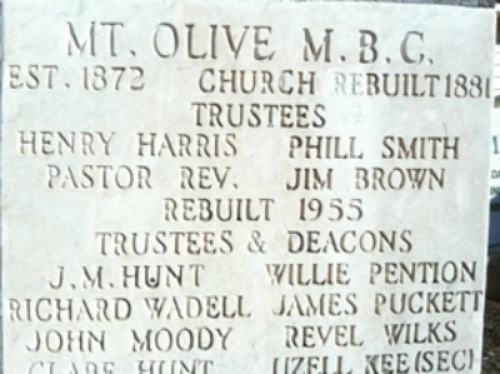

Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church

Source: Facebook page for Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church |

Around 1959, movement leaders and supporters began organizing community meetings to discuss their strategy for championing their efforts to obtain civil rights. They could find no suitable place to hold such meetings because most of the local black churches were afraid their churches would be burned and that they would suffer other reprisals from whites if activists held their meetings there.

However, the congregation of Mt. Olive MB Church did not succumb to fear, but graciously offered their small wooden church to activists for civil rights meetings.

Viola McFerren on Mount Olive Baptist Church

2002 Documentary Project on Fayette County, TN: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries.

James Puryear

Source: Photograph, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries |

Almost from the beginning of the evictions of the sharecroppers that started in the early 1960s, James. Puryear, a long-distance truck driver, and William Puryear, James' brother, informed communities in Kansas City, Missouri; Atchison, Missouri; and Kansas City, Kansas of the plight of African Americans in Fayette County. These communities responded by collecting clothes and food for distribution to evicted families living in Tent City as well as other needy individuals in Fayette County.

James and William Puryear then drove these collected items to Fayette County for distribution. Puryear and his brother's efforts helped to keep families fed and clothed when these families had no means of support.

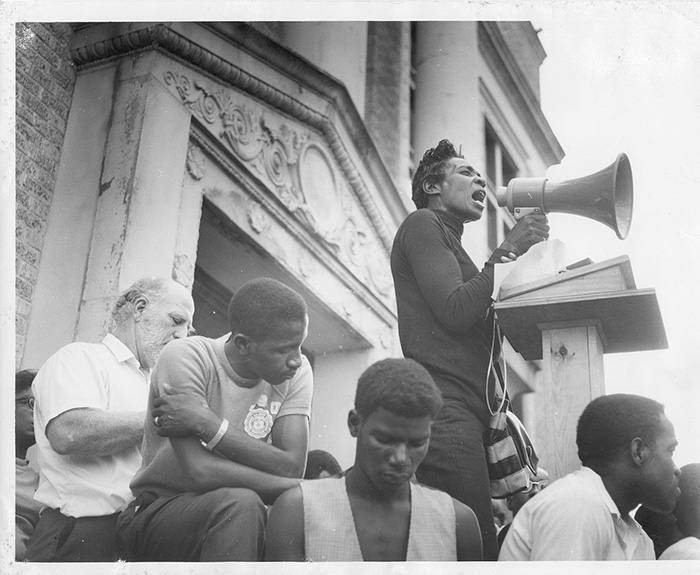

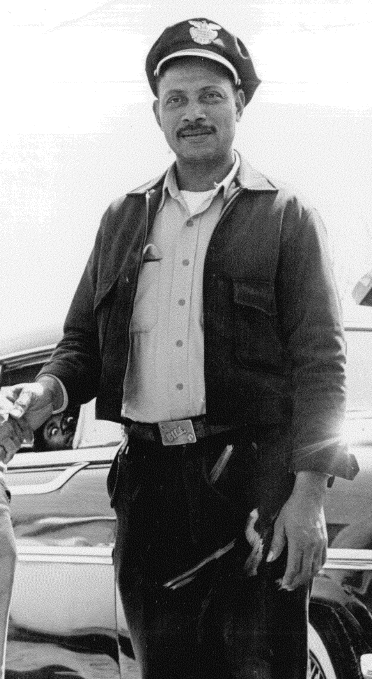

Terry Sain

Source: Memphis Press Scimitar August 26, 1969. Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries. |

Sain was a young man during the 1960s and was a leader of the young people in Fayette County.

He encouraged youth to participate in demonstration marches and led youth in the integration of restaurants and other public facilities.

Sain and others began participating in demonstration marches as early as 1962 and continued throughout the late 1960s.

Lenell Settles

Lenell Settles worked with Terry Sain during the 1960s to encourage young people to

participate in demonstration marches and the integration of public restaurants and

other public facilities.

Lenell Settles worked with Terry Sain during the 1960s to encourage young people to

participate in demonstration marches and the integration of public restaurants and

other public facilities.

Levearn Towles

Source: Copyright Dr. Ernest Withers Sr. of the Withers Family Trust |

Levearn Towles is the son of the late Shepard Towles, the farmer who provided land for evicted sharecroppers to erect tents for homes. In 1960, Towles, after registering to vote, was evicted from a farm owned by whites. From 1961 to 20--, the year the League was dissolved, Towles was a member of the Leauge. Throughout the years, he has raised money to meet the League's expenditures and provided enthusiastic support for the League's mission.

Levearn Towles on Eviction and Home

2002 Documentary Project on Fayette County, TN: Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries

Shephard Towles

Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust |

Shephard Towles, who owned his land, offered his farm first to the Mary and Early B. Williams family and then to dozens of other families who were later evicted from white farms for registering to vote. Despite having a large family himself and his own responsibilities, Towles helped rescue families who were in great need of help. Towles' generosity and courage helped to provide land to families that would, otherwise, have been homeless.

Simon Wilkerson

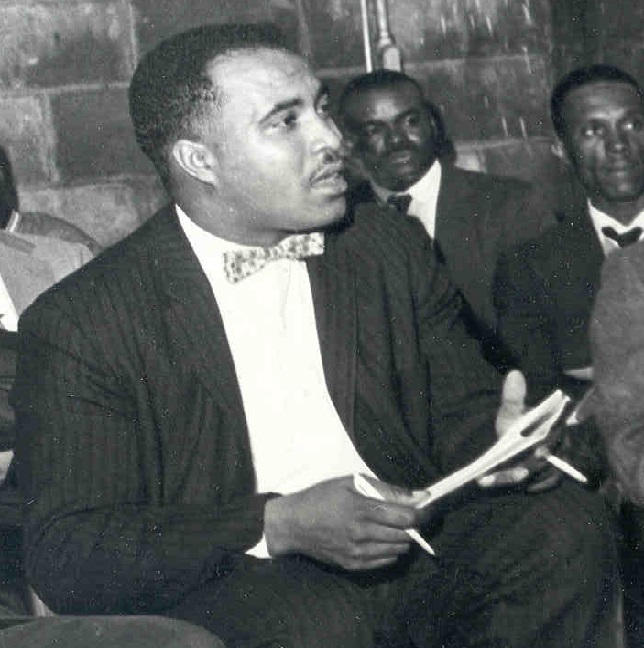

Source: Photo of Wilkerson speaking at a 1966 march. Tim Hall/Personal Collection

Simon Wilkerson and his wife Ola B. were parents of children who, in 1965, were part of the class of plaintiffs who filed suit to desegregate Fayette County schools in John McFerren Jr v. Fayette County Board of Education. In the northern section of Fayette County, where he lived, Wilkerson worked for voter registration and worked for the election for African American candidates for public office. When the Fayette County Economic Development Commission (FCEDC) was being organized, Wilkerson and Viola McFerren lobbied for black representation on the Commission, and Wilkerson and McFerren were included among the Commission's four incorporators.

The Wilks-Maclin Family

Source: Photo of Katherline Maclin, Tim Hall / Personal Collection. |

Starting in the early 1960s, Wilks "Flippin" Maclin joined in the League's mission in advancing the cause for civil rights. Mr. Maclin actively encouraged and campaigned to have his family members and his community support the League, its mass demonstration marches, and its efforts to increase voter registration.

His daughter Katherline Maclin and his granddaughter, Eva Maclin, were part of the first group of Black students to attend what was then the all-white high school, Fayette County High School. Katherline and Eva, like the other students who integrated, endured the wrath of both the white students and school officials who were against integration.

Early B. and Mary Williams

Source: photo on left is Early B. and Mary taken by the Hook's Institute in 2006. |

In the fall of 1959, Mary and Early B. Williams were evicted from the Leatherwood farm, which was owned by a white family, because they had registered to vote. In 1960, they were the first family to move onto Shepard Towles' property, where they made their home in a tent. Approximately two weeks after moving to Towles' farm, a group of white youth shot into Tent City, striking Early B. Williams in his arm as he was lying in his bed. Before the end of 1960, Mary and Early B. Williams' extended family members were also evicted from surrounding farms owned by whites and found shelter in tents on Towles' farm. The dire living conditions and lack of employment created great hardship for the Williams' and their extended family.

Eddie T. and Alice Williams

Eddie T, and Alice Williams provided housing for numerous student activists, many

of whom were white. During the 1960s students from Cornell University, Oberlin College,

University of Chicago and other schools came to Fayette County to work in the Movement.

At that time, there was a shortage of housing because even blacks who had lived in

Fayette County for their entire lives had difficulty finding suitable housing. Nevertheless,

the students' assistance was needed by Movement leaders and Eddie and Alice Williams

housed numerous students during this period despite having a large family themselves.

Eddie T, and Alice Williams provided housing for numerous student activists, many

of whom were white. During the 1960s students from Cornell University, Oberlin College,

University of Chicago and other schools came to Fayette County to work in the Movement.

At that time, there was a shortage of housing because even blacks who had lived in

Fayette County for their entire lives had difficulty finding suitable housing. Nevertheless,

the students' assistance was needed by Movement leaders and Eddie and Alice Williams

housed numerous students during this period despite having a large family themselves.

Eunice Wright

Source: Ernest Withers League photo. |

Starting in 1965, Eunice Wright began to provide activists who arrived to participate

in the movement with much-needed housing throughout that decade. She continued to

provide housing throughout the 1960s to those persons who returned to continue their

work. Wright was outspoken in her efforts to promote the Movement's civil rights agenda;

among other things, she encouraged voter registration, participated in demonstration

marches, and supported the League's effort to integrate public schools.

Allen Yancey Jr.

Source: ©Dr. Ernest Withers, Sr. courtesy of the Withers Family Trust. |

From the beginning of the Movement, the League's board formed a cadre of advisors,

that included Allen Yancey, Jr. Yancey was a local Fayette County teacher who also

taught on the college level. Because of their education and life experiences outside

of Fayette County, the League board believed that these local advisors could provide

invaluable advice to League on how best to organize the community, get assistance

to evicted families and maximize the exposure to the nation of the plight of the evicted

families.

Allen Yancy on Registration