Hypostyle

About the Reliefs and Inscriptions

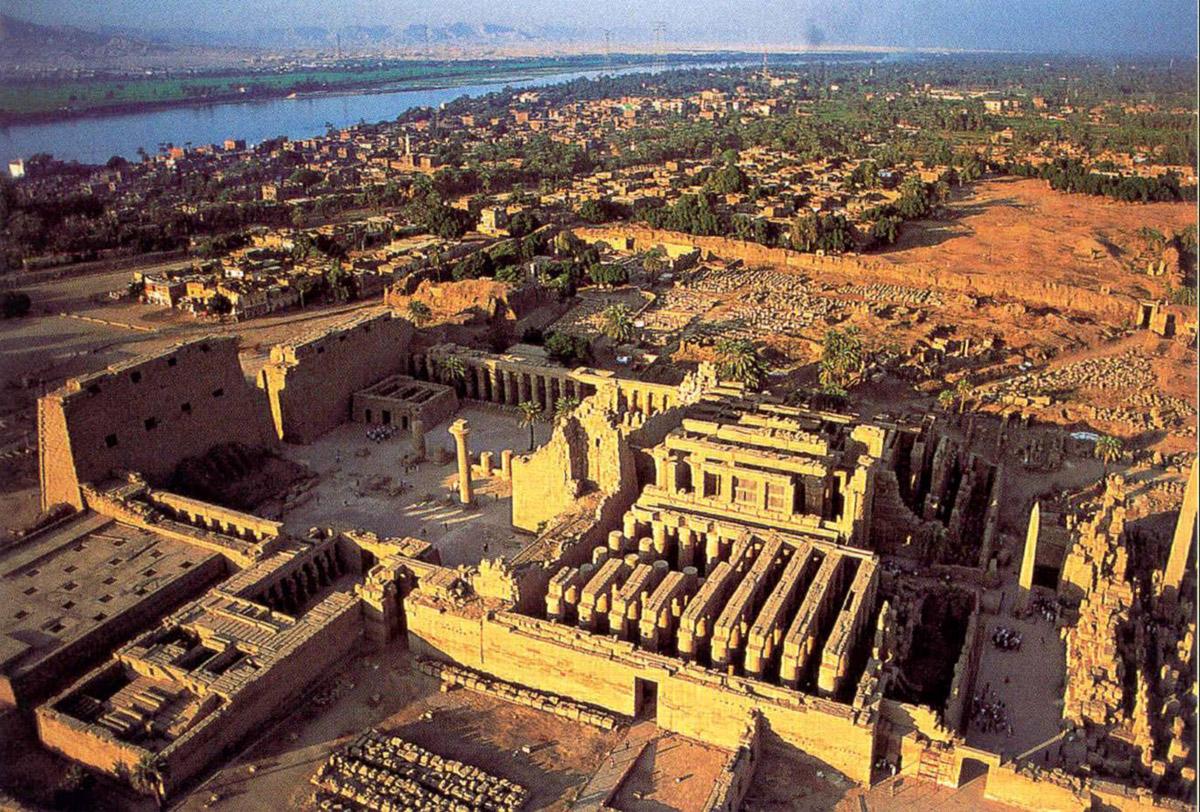

OverviewNot only is the Great Hypostyle Hall the grandest of such halls (at Karnak and throughout all of Egypt), it is also the most richly decorated. Pharaohs Sety I, Ramesses II, and their successors commanded their artisans to cover its walls and columns with hundreds of religious scenes, literally acres of relief carvings, including scenes of historical and religious significance along with accompanying hieroglyphic caption texts. This ritual art represents a sample of the sacred activities that Pharaoh and Amun’s priests enacted within the temple, from the daily sacrifices to its main god Amun-Re to yearly festivals during which Amun left Karnak and visited other temples in ancient Thebes. In other scenes, Pharaoh appears before the gods to receive their approbation of his earthly dominion over Egypt. They crown him with various diadems, invest him with scepters and other insignia of rule, and even pour water over him in a kind of pharaonic baptism.

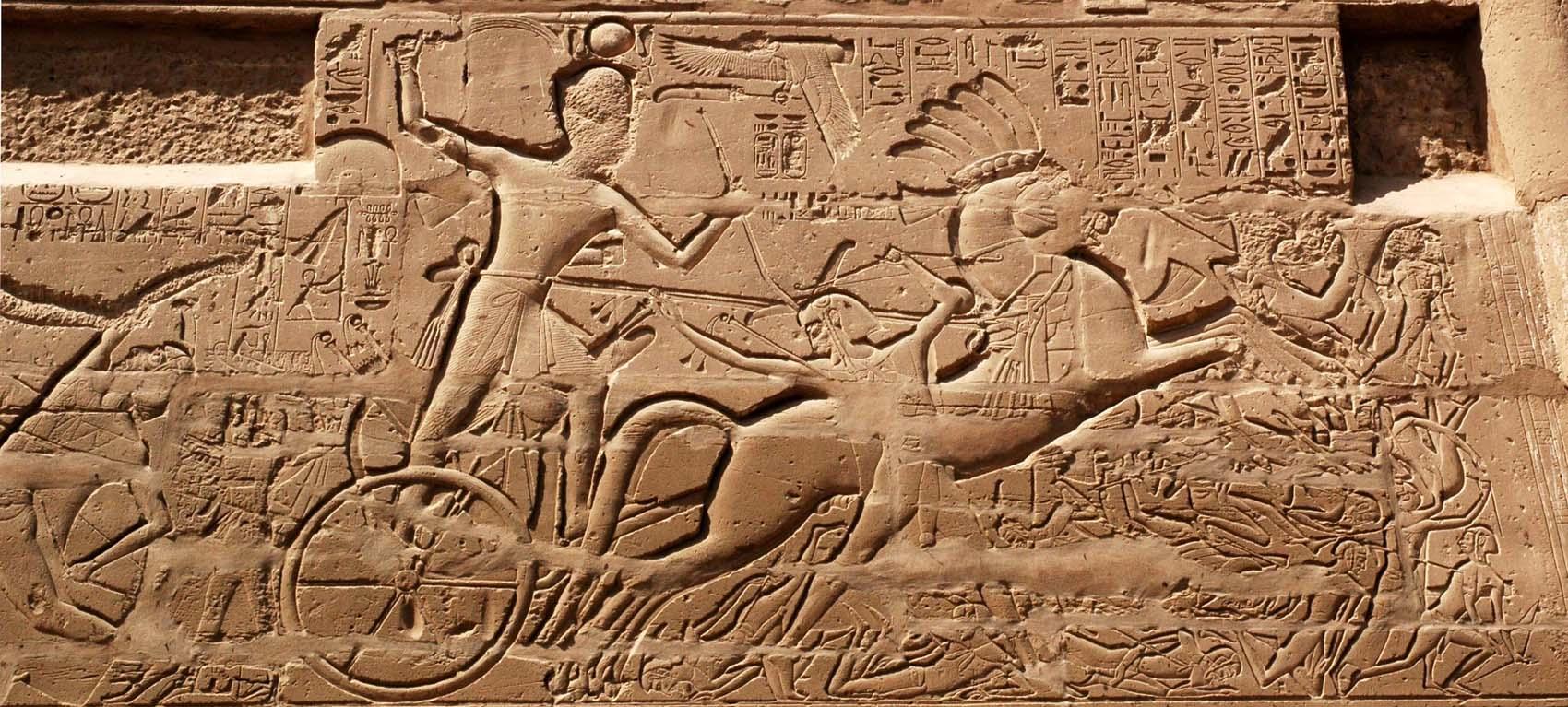

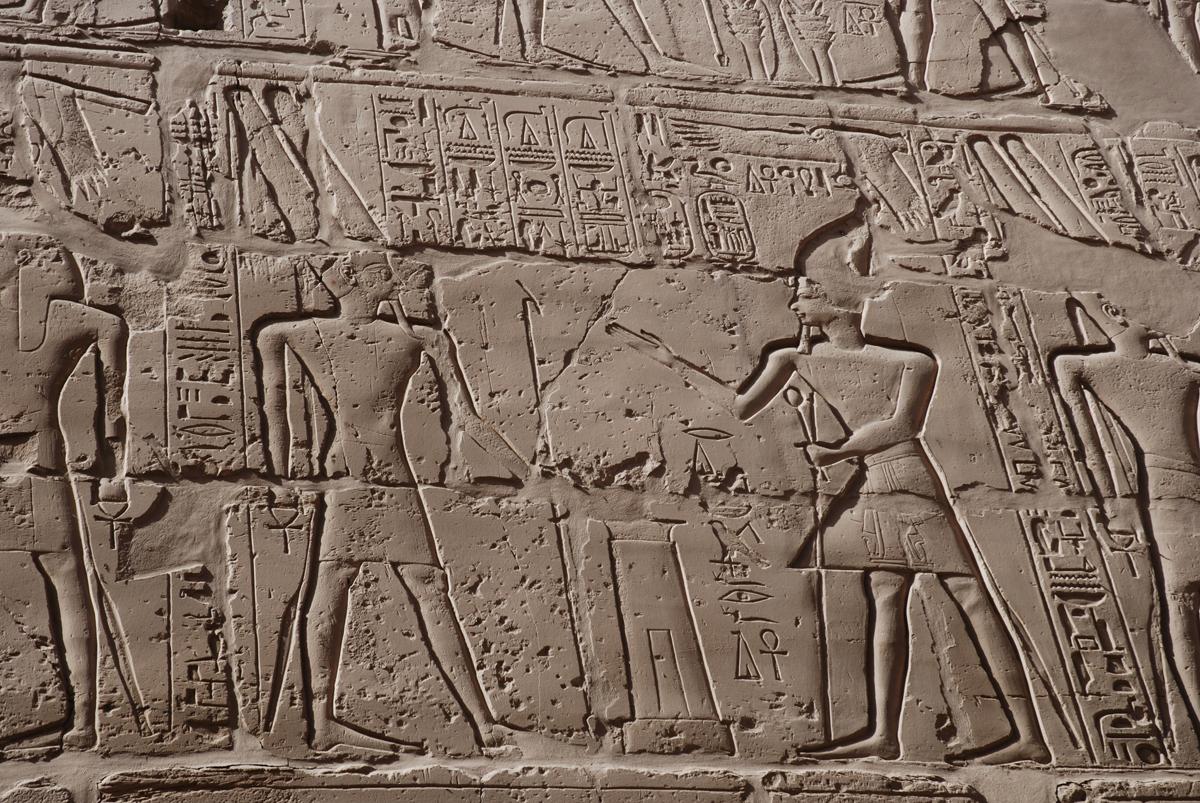

Every space on the columns, the base of the walls, the gateways, and all exposed surfaces of the architraves and clerestory roof are covered with hundreds of additional decorations, including long dedicatory texts, stereotyped friezes of royal titles, and heraldic devices. Many of these inscriptions are highly repetitive and stereotyped, particularly the endless royal cartouches and strings of kingly titles that Ramesses II and especially Ramesses IV added to the columns. Outside, on the building’s northern and southern exterior walls, panoramic battle scenes sculpted in bold sunk relief immortalize the wars of Sety I and Ramesses II in ancient Syria, Canaan, Lebanon, and Libya. Intended to glorify the king’s role in warfare and to symbolize the triumph of the forces of order over chaos, these scenes portray Pharaoh as a larger-than-life superhero singlehandedly defeating his foreign enemies. After his inevitable triumph over the foe, the king presents the spoils of victory and prisoners of war to Amun-Re . Although highly bombastic, such monumental propaganda constitutes vital evidence for Egypt’s foreign relations in the 13th Century BCE, especially in the years prior to Ramesses II’s peace treaty with the Hittite Empire.

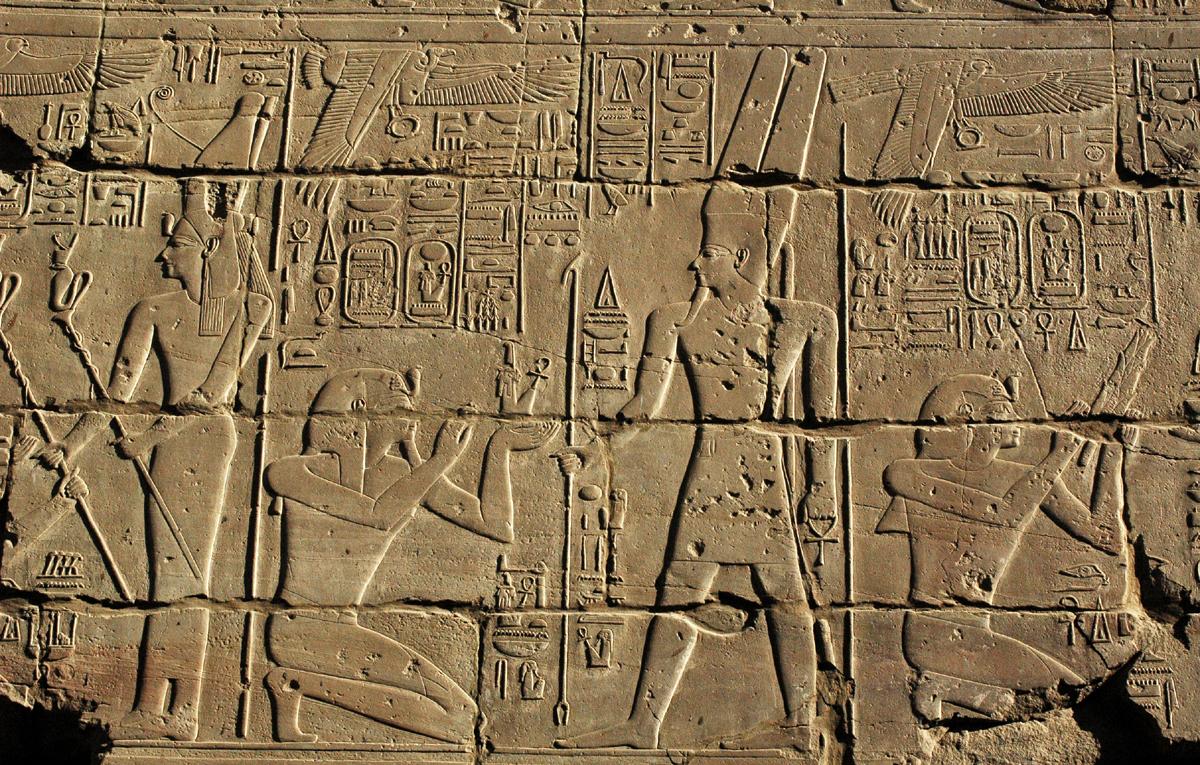

Ritual Scenes and their SequenceInside the Hypostyle Hall, religious themes prevail, with pictorial scenes showing Pharaoh in the company of Egypt’s gods. A seemingly endless progression of religious scenes unfolds on every wall, column, and gateway, each depicting the king performing some ritual act in the presence of one or more gods. Dense columns of hieroglyphic texts crowd the space above the figures’ heads and sometimes between one figure and another. But what do all these images mean? Do they form some continuous narrative or tell a story? On every wall, ritual scenes unfold at several levels, called registers, stacked one atop the other. Most walls have four or five registers of individual scenes that are contained within their own “cell,” like a comic strip. Altogether, each wall gives the appearance of a mosaic or collage of distinct cells, but are they really like a giant comic book or graphic novel etched in stone?

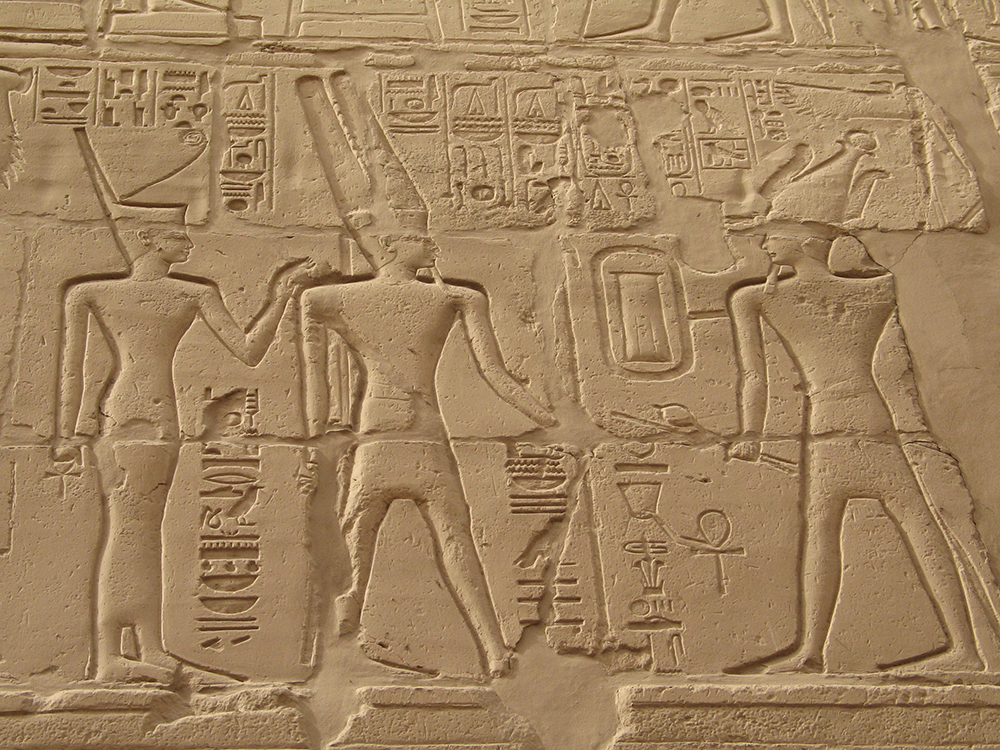

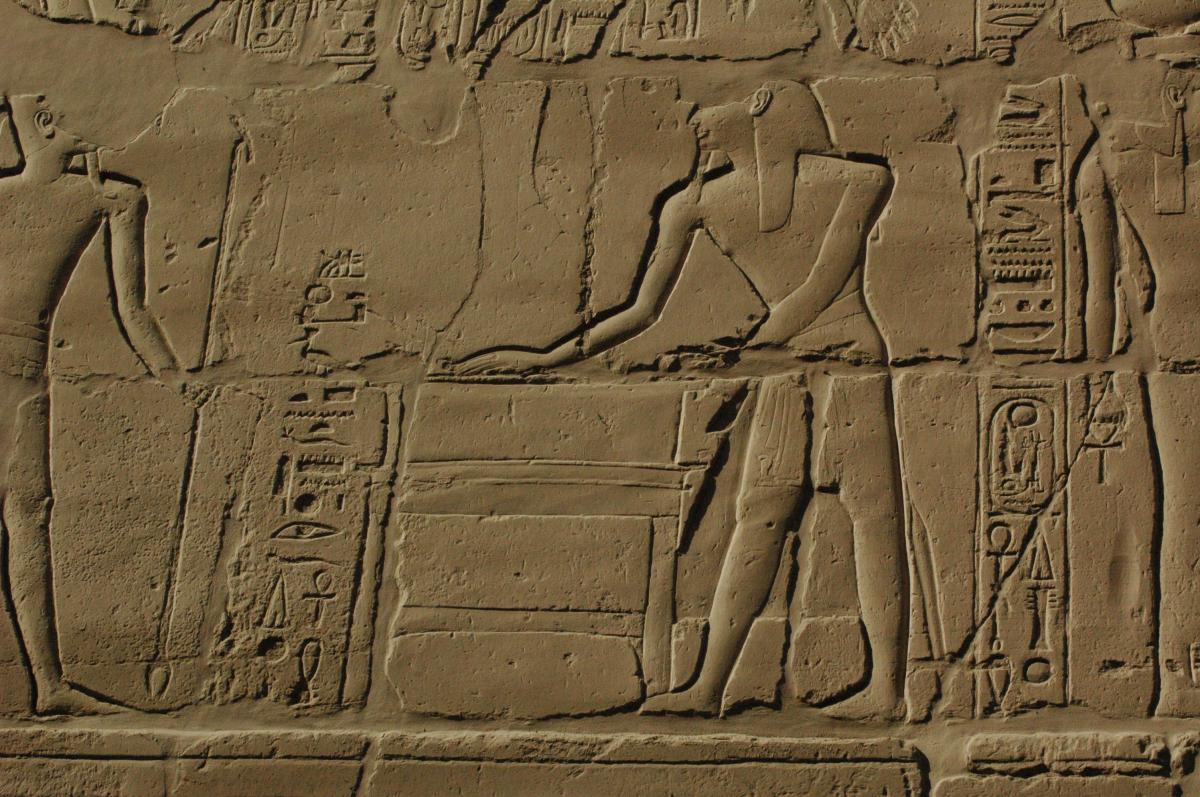

Every scene depicts a complete ritual event and stands by itself as a complete sacred act. A collection of scenes on a whole wall, or even in a single register, do not necessarily form a continuous narrative, yet smaller groups of episodes may link a sequence of closely related cultic acts to describe a larger ceremony. Visual clues underline the apparent individuality of the scenes. Not only does Pharaoh accomplish different sacred tasks from one episode to the next, he changes his physical appearance as well by donning different crowns and costumes. The gods he worships and their appearance also varies from scene to scene. Such inconsistencies in the actors and their physical description need not indicate that smaller groups of scenes do not link together to form a broader narrative. We can read brief sequences of events narratively from one scene to the next, as with the king’s journey from his palace to Amun’s temple in a cluster from the south wall. Here, Ramesses II departs from the palace where he meets the god Khnum, who purifies him with water. Next, he is led hand in hand by the gods Atum and Monthu into the temple, where he kneels in Amun’s shrine and receives his blessing while the god Thoth and goddess Seshet present him with palm fronds and hieroglyphic characters symbolizing a long reign of many years and countless jubilee festivals. Foundation RitualsLonger ritual sequences may consist of several related episodes, as with the temple foundation rites depicted on the west wall. Here Ramesses II conducts a series of rites to construct and dedicate a new temple to Amun. Arranged one after the other on the second register from ground level, these progress from right to left in six episodes:

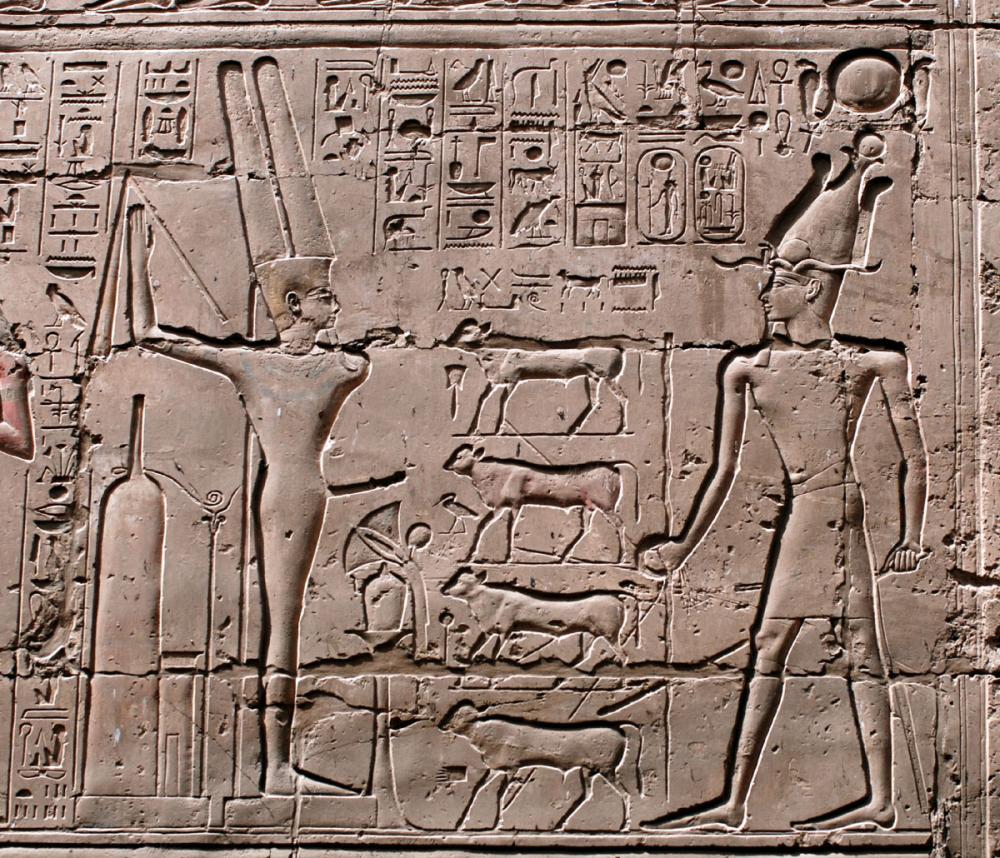

Amun is present in every case to witness Ramesses II’s acts, yet in the final episode of the foundation ritual, neither appears. Instead Sety I dedicates a hecatomb offering to the Memphite god Ptah. With this sequence, Ramesses never intended to commemorate actual events, either to show current acts or imagine future ones. Instead, these scenes illustrate timeless and idealized ritual acts that any king might perform at any time. In other temples, the foundation ritual sequence can include various numbers and groupings of these and related scenes. Varieties of Ritual ScenesModern visitors are easily overwhelmed by the confusing jumble of religious scenes on the walls and columns of the Hypostyle Hall. They seem to have little observable relationship to each other except the repetitive appearance of Pharaoh before the gods. Even for Egyptologists, these sequences too often appear random. Smaller groups can be read together as a narrative, but the larger “order of service” of these rites across whole walls or the entire building often still eludes us. Nevertheless, we can discern larger themes in the decoration including: festival celebrations; the daily cult ritual enacted on behalf of the god in his shrine; and themes centering on rites of pharaonic kingship. Even when there is no clear relationship between one episode and the next, nearly all of them share a common iconographic structure or pattern of activity. Most can be classified based on what the king is doing on behalf of the gods, or vice versa. A few distinct categories form the bulk of what we see according to the ritual event and while details vary widely, most scenes fall into a limited range of basic themes in which Pharaoh does one of the following:

While there are literally dozens of other categories of ritual scenes, including the foundation rites or special acts connected to festivals or the daily service on behalf of the god’s cult image, the largest percentage will belong to the groups listed above. Yet within these relatively few categories, there will be endless variety in the mix of gods, royal costumes, hieroglyphic texts, offerings, and ritual paraphernalia. Scenes related to festivals, both real and idealized, also bulk large in temple wall art. Processional scenes involving sacred barks of the Theban Triad tend to be the most elaborate of these, as Pharaoh escorts the bark of Amun and its cortège of bearer-priests while those of Mut and Khonsu follow behind, or as he makes various offerings to the barks once they are installed in the temple’s holy of holies. Other rites seem to be of a celebratory nature, but texts accompanying them do not refer to any specific festival like Opet or the Valley Feast as with the bark procession scenes. This collection of miscellaneous acts includes:

Egyptian temple worship was based on the idea of a mutually beneficial relationship between humanity and the gods. Pharaoh was the ultimate intermediary with one foot in the divine realm and another in the human world. Just as he built temples and performed ritual acts for their “care and feeding,” the gods in turn could do good turns for his benefit. These divine benefactions on behalf of the king are symbolized by a class of scenes intermixed with the rest. In all of these, the gods are the actors and Pharaoh is the recipient of their blessings:

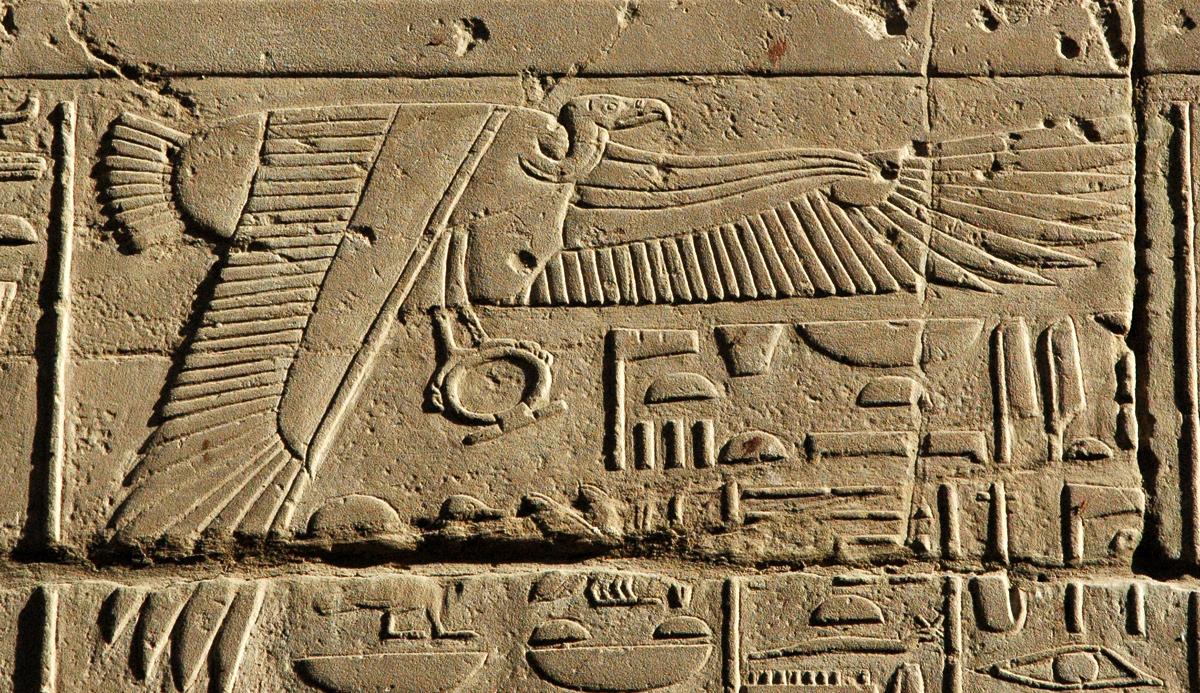

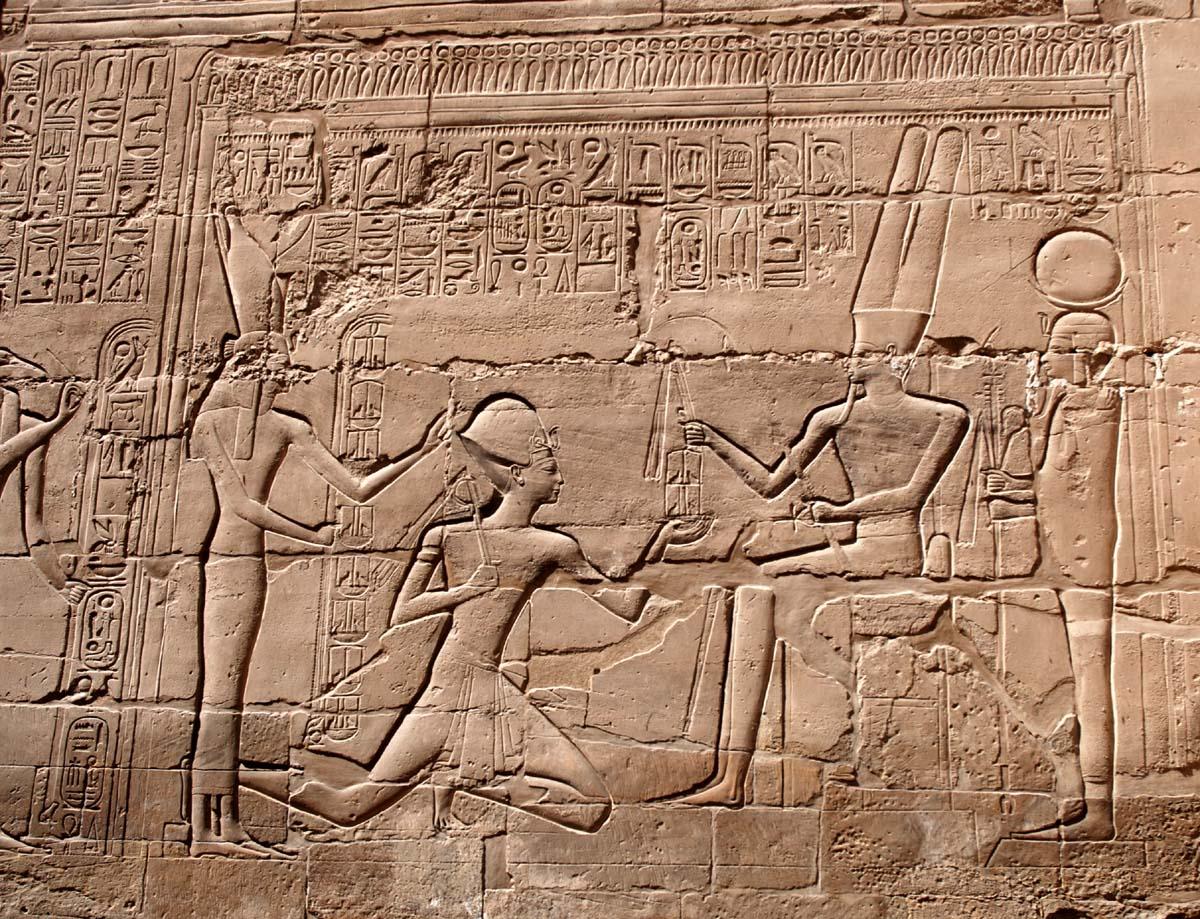

Most of these rites can appear separately or be combined together, as shown on the east wing of the south wall where Ramesses II kneels to receive years and jubilees from Amun-Re, Mut, and Khonsu while Thoth inscribes his name on the Ished-tree. Structure of Ritual ScenesDespite their infinite variety of iconographic details and combinations of hieroglyphic texts, all these ritual scenes possess a common structure allowing the viewer to decode them. Pharaoh appears on one side of the scene, confronting one or more deities who face him. Normally, the artists carefully designed the image so that the king appears to have arrived from outside the temple and faces towards its interior, while the gods resting within it face towards the outside world. The principal deity always faces the king directly, while secondary divinities stand behind him. Attendant deities are often female or are males that are somehow subordinate to the premiere one. Less often, another deity stands behind the king and always faces in the same direction that he does. In the middle of most ritual scenes, an altar bearing offerings stands between the king and the main god. These vary from heavily laden tables piled high with an assortment of bread, meat, fruits, flowers, and incense pots to a single hourglass shaped table-stand bearing a libation vase and small bouquet of flowers. While such offering tables may be the central focus of the king’s cultic act, when he dedicates them, in other cases they are incidental to his rite and serve mainly as “space fillers.” Offering stands can even be entirely absent due either to lack of space or when they are replaced with other bulky objects crucial to the ritual as when Pharaoh drives the four calves or consecrates Meret-chests. Above the king’s head, except where space is lacking, there usually hovers a raptor or solar symbol as manifestation of a protective deity. Vultures commonly represent the goddesses Nekhbet of Upper Egypt or Wadjet of Lower Egypt. Nekhbet’s primary form was as a vulture while Wadjet was a serpent goddess, sometimes with a cobra’s head, but who also appeared as a vulture. Falcons always represent the Behdetite, a form of the kingly god Horus. Solar disks, often with two uraeus cobras and sometimes with hieroglyphic signs for life and dominion suspended from them, are further incarnations of the Behdetite.

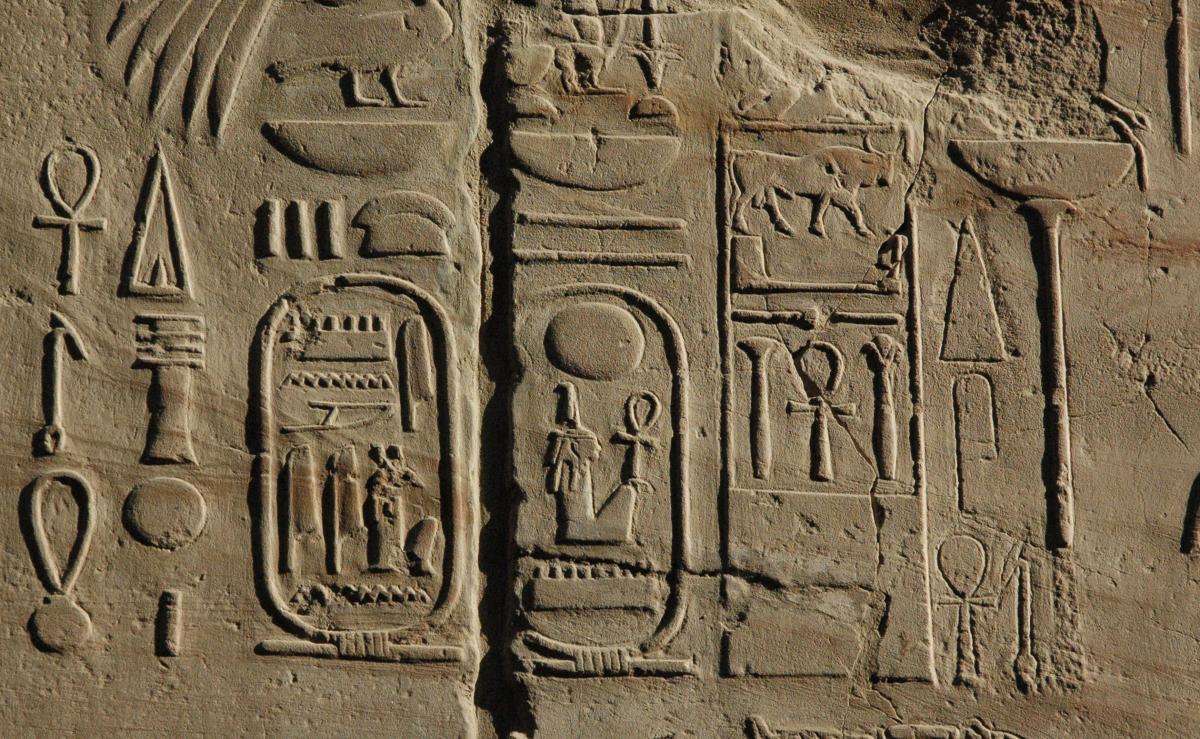

In the upper half of the scene, one finds columns of hieroglyphic texts grouped by theme. Above the pharaoh himself, the texts contain one or more of his five royal names and titles, especially his two cartouche names enclosed within their distinctive ovals and sometimes his Horus name inside a tall rectangular “box” on which a falcon hieroglyph rests.

Accompanying texts can also give various other titles and epithets. In most scenes, further texts connected to Pharaoh express wishes for divinely-given benefactions, describing him as one “given life, prosperity and health (etc.)…like the sun god forever.” Behind him might be a column of hieroglyphs expressing a further wish that “every protection of all life, stability and dominion, all health, and all joy might surround him like the sun god.” A separate text frequently appears in the lower middle part of the scene between the king and god. Called a “label text,” this inscription serves as the title of the scene itself, referring to the king’s ritual act. Label texts announce what the king is doing and for which god. They further assert that he obtain some benefit in exchange for his gift to the deity, such as to be “given life.” Typical examples include:

Above and around the gods and/or goddesses in the scene are hieroglyphic texts bearing their names and epithets, followed by brief speeches in which they confer their blessings on Pharaoh in exchange for his cultic acts on their behalf. Divine speeches frequently begin with the phrase “words spoken” or “words spoken by god N.” Since Egyptian texts lacked punctuation, these formulae are essentially quotation marks but also remind the priest or even the gods themselves to recite these favors aloud. A few of these brief formulaic statements include:

Dozens of other benefactions in countless arrangements appear in divine caption texts throughout in the Great Hypostyle Hall. As wall space allows, both the primary and secondary deities pronounce similar blessings, and columns of texts listing their invocations may be sandwiched between or behind them. In more spacious tableau, the gods give longer, less formulaic speeches. Often praising Pharaoh’s achievements as a builder of temples and for donating rich offerings, they are more effusive—and detailed—in promising him endless blessings for his piety.

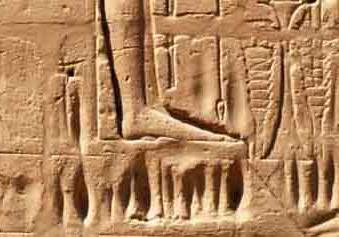

Finally, brief caption texts beside the protective raptor or Behdietite solar disk above Pharaoh feature the god’s name and epithets, often with the phrase “as he/she gives life, prosperity, etc…” Marginal Decoration, Graffiti and Popular Religious PracticesA confusing patchwork of inscriptions blankets every surface of the Hypostyle Hall, especially on most of the 134 columns. Responsibility for the density of this embellishment lies not just with the Hall’s builders, Seti I and Ramesses II, but with a number of their successors. Disregarding the balance between inscribed and blank surfaces which would allow inscriptions to be seen to advantage, Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and the High Priest of Amun Herihor filled empty spaces on columns, walls, and gateways with new texts. They applied bandeau texts listing strings of their royal titles and formulaic dedication texts on gateways and at the base of the walls. Ramesses IV systematically embellished large portions of most of the 134 columns with bandeau texts and friezes of his royal cartouches, all repeated endlessly. Indeed, his cartouche names appear literally thousands of times!

The Ancient Egyptian practice of adding new inscriptions to older buildings, even at the cost of erasing the name of the original builder, is strange to modern viewers who are likely to accuse the offending pharaoh of theft. Imagine if a modern American president tried to add his name to the Washington Monument or replace Lincoln’s statue with his own in the Lincoln Memorial. The public would be outraged! But such practices were considered perfectly legitimate, even normal, in Egyptian antiquity. Egyptians added new inscriptions to existing monuments for a variety of reasons. As with most of Ramesses IV’s inscriptions, a king might do so without actually removing the name of his predecessors. Midway through his 67 year reign, Ramesses II added hundreds of new inscriptions to

the columns and nave of the Hypostyle Hall, sometimes erasing the names of his long-deceased

father Sety I in the process. Yet Ramesses acted not out of spite or hatred of his

father, but in celebration of his own great series of jubilee festivals. His successors,

including Ramesses IV and the High Priest of Amun-Re Herihor, added marginal inscriptions

on undecorated parts of the columns, seeking to associate themselves with their illustrious

predecessors Sety I and Ramesses II, but without erasing their names. In some cases,

however, Ramesses VI reinscribed Ramesses IV’s cartouche names with his own, but more

often, he left them untouched.

|