The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change

The Civil Rights Era Begins in Memphis

In 1954, the national NAACP won the hard fought court battle Brown v. Board of Education. This case ruled that applying the concept of "separate but equal" to public schools was not constitutional. While the ruling was supposed to end legal segregation in schools, most states and cities, including Memphis and Tennessee, developed ways to circumvent the law. Still, African Americans saw the ruling as the dawn of a new day. In addition, Memphians also found hope after the death of Boss Crump, who died only five months after this landmark Supreme Court case. Crump's death and the decline of his machine led to a new era of Black independent politics. With no one to replace Crump, Blacks seized the opportunity to gain political power. That same year, three Blacks –William C. Weathers, Benjamin Hooks, and T.L. Spencer – ran for elected positions. Although they did not win, their campaigns yielded a large increase in registered Black voters.

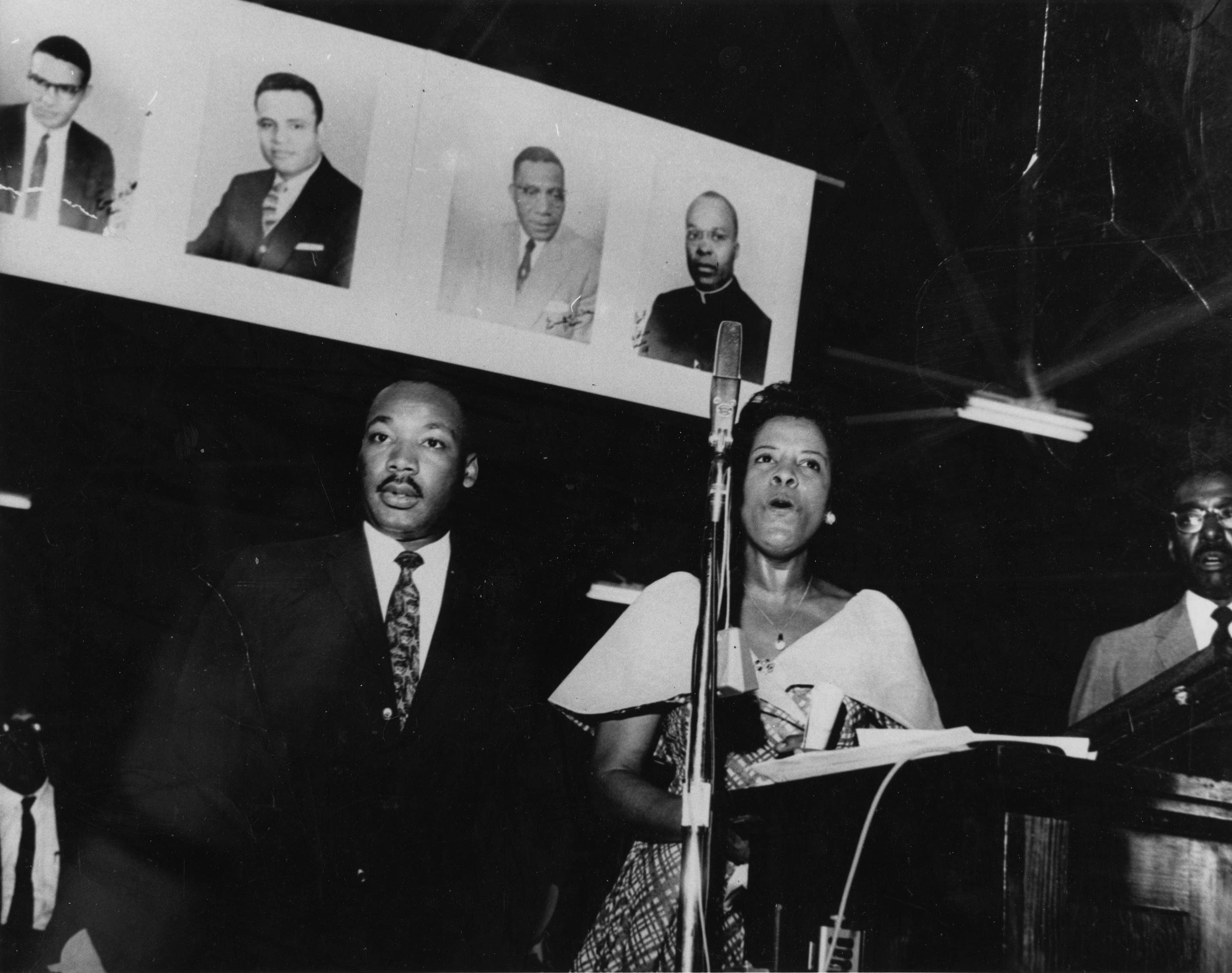

Subsequent elections and voter registration drives led to the largest push for political power by African American leaders to that date. Black Democrats and Republicans joined together and strengthened their political power by resurrecting the defunct Shelby County Democratic Club. The club served as an independent political party, coordinating with different civic clubs in voting precincts with the goal of getting Black candidates elected. They made their most aggressive push for political representation in 1959 with what became known as the Volunteer Ticket. It was local, all-Black, and independent of the major political parties. That August, attorneys Benjamin Hooks, Russell Sugarmon and A.W. Willis, as well as Reverends Roy Love and Henry Clay Bunton ran for political office on the Volunteer Ticket. One of the ways in which "the Ticket" raised funds and garnered support was hosting a rally at Mason Temple at the end of July 1959 that featured the famous gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, backed by a 1000 member choir drawn from local churches and an uplifting speech from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

King stressed the importance of supporting the Volunteer Ticket. King told the crowd that he "had never seen such enthusiasm at a meeting of Negroes." Unfortunately, the Volunteer ticket failed to get any Black candidates elected but succeeded in increasing the Black vote to 55,000 and ushering in a new era of independent Black politics.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the local NAACP was led and controlled by pastors and churches who did not want to do anything that would anger the Crump Machine. During this time, the organization was not very active - politically or socially. Things began to change in the mid-1950s when returning veterans and recent college graduates assumed leadership. Most of the new leaders were former members of the more active youth NAACP before and during college. Attorney H.T. Lockard became the president of the NAACP at the beginning of 1955. By then, the organization was led by lawyers such as Benjamin Hooks, James F. Estes, Russell Sugarmon, A.W. Willis, and Ben F. Jones. They attracted a young accountant named Jesse Turner, who was one of ten Black Certified Public Accountants in the nation. Dentist Vasco Smith joined the branch upon his return to Memphis in 1955. This new crop of leaders came back to Memphis with the intention of making it a truly integrated society.

After the Brown v. BOE Supreme Court decision, most NAACP branches around the country began fighting for school desegregation at the high school level. This was dramatically played out in Little Rock, Arkansas where the violence and harassment towards students garnered national attention and resulted in President Dwight Eisenhower federalizing the National Guard and sending the 101st Airborne to the city by an Executive Order. The Memphis NAACP wanted to avoid this kind of reaction and developed a plan that would keep children out of harm. In 1957, Maxine Smith and Laurie Sugarmon, the wives of Vasco and Russell respectively, applied for graduate school at the city's all-white Memphis State University. Smith had previously received a Master's degree from the prestigious Middlebury College, while Sugarmon had graduated Phi Beta Kappa at Wellesley College. Despite their credentials, both were rejected by the University. Less than a decade later, Sugarmon became the University's first Black faculty member. Allegra Turner—a Catholic and wife of NAACP President Jesse Turner—fought to have her children admitted to private Catholic schools during segregation. Christian Brothers High School became the first desegregated high school in Memphis (public or private) when Jesse Turner Jr. enrolled as a freshman. In this era, women led the charge against the barriers of segregation. Some, like Maxine Smith, even assumed leadership roles. In 1962, Smith became the local NAACP's first Executive Secretary, a paid professional position that was rare in the South.