The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change

Memphis and World War II

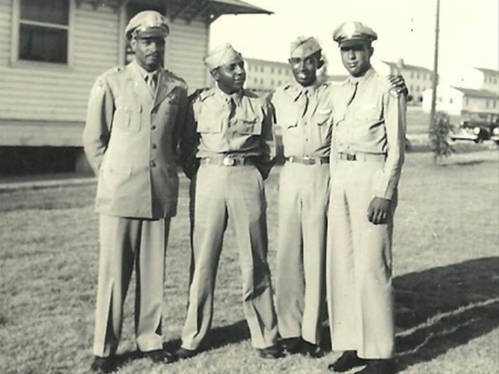

During World War II, 1.2 million African Americans served in the armed forces. The majority of these men and women served in segregated units and most did not fight in combat. However, African American combat units, such as the Tuskegee Airmen, the 92nd Infantry Division, and the 761st Tank Battalion, inspired military troops and African American citizens at home.

At home, the black press promoted the "Double V" campaign with the theme "Democracy: Victory over discrimination at home, and victory over fascism abroad." After labor leader A. Phillip Randolph threatened a mass march on Washington, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which became known as the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). The commission regulated defense industries to make sure none discriminated on the basis of race, creed, color or natural origin.

Memphians participated in scrap metal drives at local theaters, such as the Palace on Beale Street, and war bond drives. In one successful war bond drive, led by George W. Lee, known as the "mayor of Beale Street," black Memphians raised $303,000 to build a B-24 Consolidated Liberator bomber. Luke Weathers, a 1939 graduate of the city's Booker T. Washington High School, flew a P-51 Mustang with the Tuskegee Airmen. Weathers, who flew 71 missions in Europe over in a fourteen-month period, was honored with a parade down Beale Street and was the first black man in the city's history to receive a ceremonial "key" to the city.

After the war ended, the administration of President Harry S. Truman appointed a Commission on Civil Rights, which issued its report "To Secure These Rights" in 1947. The report's recommendations included strengthening the civil rights division of the Department of Justice, creating a permanent FEPC as well as anti-lynching and anti-poll tax legislation. In 1948, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which eliminated segregation in the armed forces. Sixteen years later, the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the Constitution abolished poll taxes.

A large number of African Americans who had left Memphis during in the 1930s returned in the late 1940s and early 1950s as experienced professionals with military training and college educations. Disappointingly, they returned to a Memphis that was much the same as the one they had left—highly segregated and politically exclusive. Some small but significant changes were apparent. In 1948, nine African American men were appointed to the city's police force – the first to patrol the streets since the late 1800s. Four years later, led by George W. Lee, the city's black Republicans organized support for Dwight D. Eisenhower's successful presidential campaign. However, two major events occurred in the mid-1950s that changed the history of Memphis.