Tent City: Stories of Civil Rights in Fayette County, Tennessee

Fayette Timeline 1961

January, 1961

Source: The Commercial Appeal: November 16, 1961. Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries. |

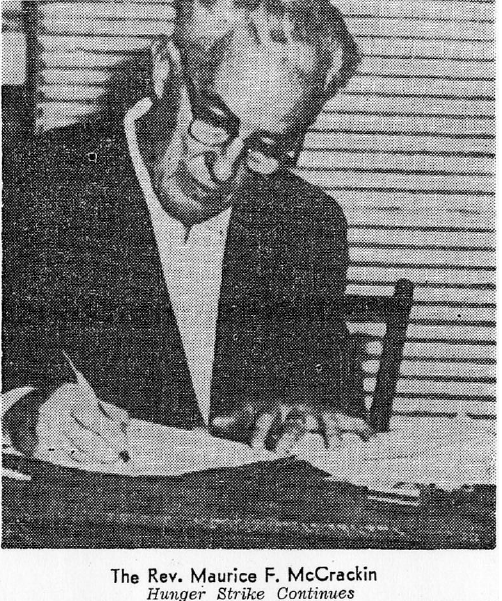

Reverend Maurice McCrackin, a Presbyterian minister, pacifist, and human and civil rights activist, asks fellow peacemakers in Cincinnati to consider providing assistance to Blacks who have been retaliated against by whites for their civil rights activities. On January 16, 1961, McCrackin and other peacemakers drive from Cincinnati, Ohio to Fayette and Haywood counties to assess the conditions of Blacks. On February 16, 1961, John McFerren (Fayette County) and Odell Saunders (Haywood County) meet with McCrackin and other peacemakers in Cincinnati to discuss how the outside activists might effectively help Blacks in Fayette and Haywood Counties struggling for civil rights. The group agrees to call McCrackin's and the peacemakers' aid "Operation Freedom." "[M]ost liked its upbeat quality and its allusion to the Freedom Rides, which were going on in the South."

Virgie Hortenstein, an avid supporter of McCrackin, assists in the administration of Operation Freedom. Hortenstein later leads the Fayette-Haywood Workcamps, which provide educational and employment training to poor Blacks. The Fayette Haywood Workcamp organization is chartered in February of 1968, but begins working, through Operation Freedom, in Fayette and Haywood Counties nearly a decade before being chartered. The organization is now considered inactive, but the exact date of the organization's end is unknown. Virgie Hortenstein, the leader of the organization, works in Fayette and Haywood counties until her death in the mid-1980s.

February 6, 1961

Source: Press Scimitar, August 8, 1961. Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries.

June Dowdy and John McFerren make a speaking trip to Chicago's Kenwood-Hyde Park neighborhoods to speak about the harsh conditions facing Blacks in Fayette County. John McFerren and his wife, Viola McFerren, start speaking locally and across the nation about these hardships including the Black community's fear that it will not have adequate food and clothing to survive the hardships. These speaking engagements win supporters from across the nation for the Black citizens' efforts to register to vote, resulting in food, clothing, financial and other assistance to evicted sharecroppers.

March, 1961

Source: Fayette Falcon, March 23, 1961 |

The National Baptist Convention purchases land in Fayette County to be used as housing and farm land for evicted sharecroppers. It is named Freedom Farm. Prior to the evictions, sharecroppers do not make enough money to cover all of their farming and living expenses and are often forced to borrow money from their landowners and other whites in the county to survive. These debts are recorded by the whites, and the Black tenants often are not aware of how much they owe, due in part to a lack of literacy on the part of the sharecroppers and in part to the lack of written contracts between lenders and borrowers. Furthermore, many landowners participate in corrupt practices, including paying too little for crops and recording more debt than is actually owed, in order to keep sharecroppers dependent. Freedom Farm, however, operates using strict, written contracts that track tenants' debt and rent and require regularly scheduled payments. The former scharecroppers residing at Freedom Farm find it difficult to adjust to the strict contractual agreements that regulate rent and life on Freedom Farm. This struggle is a direct result of the paternalistic and flexible nature of the verbal contracts they have previously held with white farm owners. Furthermore, mechanization and farm consolidations in the county make it nearly impossible for the farmers living here to make a profit.

March, 1961

Source: Photograph, Special Collections, University of Memphis Libraries. |

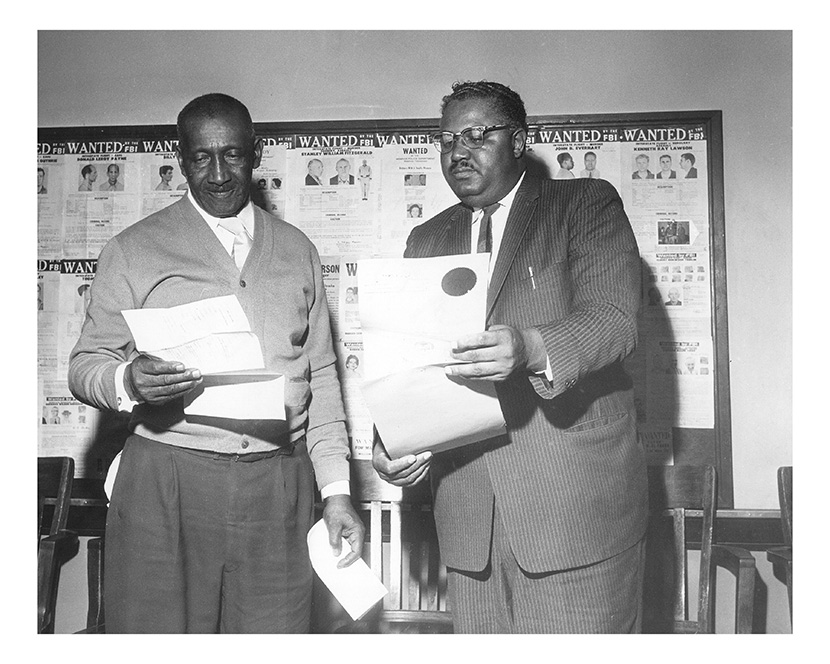

Franklin and his supporters question McFerren on the fairness of the distribution of food and clothing sent to Fayette County for needy Blacks. Additionally, Estes and McFerren quarrel over the distribution of $800 donated in 1960 from Dr. Martin Luther King's organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. McFerren insists that the proceeds received for Fayette County be spent to buy food for evicted Black families. Estes demands that the League use the funds to pay him for the substantial legal services he has provided to Black activists. Dr. King's draft letter remitting the check does not state how the funds are to be used but declares SCLC's commitment to civil rights, writing "[i]n our move toward the threshold of equality the time has come to re-double our efforts to stem the time of segregationists retaliation and persecution in Fayette and Heywood [sic] Counties."

McFerren, Estes, and Scott are unable to resolve their disputes and the League splits, with supporters following either McFerren or Franklin. These disputes are not resolved, and the alliance among McFerren, Estes, and Franklin ends. McFerren and his supporters then form another organization, The Original Fayette County Civic and Welfare League. From 1961 through the late 1970s, The Original Fayette County Civic and Welfare League moves forward with an aggressive civil rights strategy to end segregation in school and employment. It also advocates for economic empowerment of African Americans. The Original League becomes the predominant group and fights for civil rights within the county for several decades

June 14, 1961

Source: TriState Defender, December, 1960. |

President Kennedy issues an executive order sending surplus food to Fayette County. The Original Fayette County Civic and Welfare League writes letters of gratitude to President Kennedy for his help. In previous decades, white Fayette County officials declined receiving surplus food, claiming there is no need when, in fact, the popular press reported Fayette County was the third poorest county in the nation, with most African Americans living in poverty. The historical lack of outside assistance, including food, reinforced Black sharecroppers' dependency on white landowners and the segregationist practices that had held sway over them since slavery.