School of Law

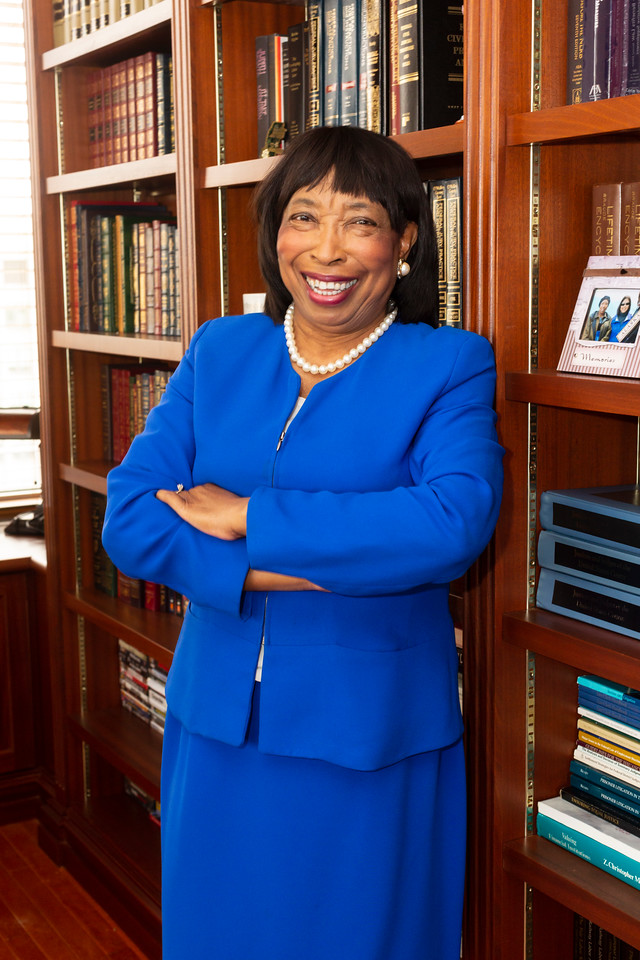

JUDGE BERNICE BOUIE DONALD HAS SPENT HER entire life breaking down barriers and being the "first" to achieve a great many things.

The term "trailblazer" does not really begin to sum up her self-forged path.

As a child, she was among the first four African American students to integrate Olive

Branch, Miss. schools. Not too long after graduating from the University of Memphis

School of Law, where she was a first-generation college student, she was elected to

the criminal division of Shelby County General Sessions Court, making her the first

female African American judge in Tennessee history. In 1988, Donald was appointed

as a judge for the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Tennessee,

making her the first female African American bankruptcy judge in the nation. Breaking

down yet another barrier, she was nominated by  President Bill Clinton to serve as the first African American female U.S. District

Judge in the Western District of Tennessee, where she remained until her present appointment

in 2010. The trend continued with that appointment as well, with President Barack

Obama nominating her in December 2010 to serve as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit, once again making her the first African American female to

sit on that court.

President Bill Clinton to serve as the first African American female U.S. District

Judge in the Western District of Tennessee, where she remained until her present appointment

in 2010. The trend continued with that appointment as well, with President Barack

Obama nominating her in December 2010 to serve as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit, once again making her the first African American female to

sit on that court.

Her lifelong tendency of being a "first" extends off the bench as well. She was the first African American and the first female to serve as president of the American Bar Foundation, the nation's leading research institute for the empirical study of the law, and formally served as the secretary of the American Bar Association, once again as the first African American woman to do so.

A common theme amongst her decisions to steadily break down barriers and advance toward more influential and powerful positions throughout her career is a surprising one, though it won't be to anyone that knows her well. In conversations, Donald often comes back to her desire to ensure those in power do not abuse it and to use her own position to help those in need.

"I wanted to be in a position of power so I could ensure that others are treated with respect by those in power," she said in a past interview with one of her former law clerks, Samara Spence. "I saw too often how people, including myself, were not always treated with respect, and it was simply unacceptable."

EXPANDING UPON THAT vision, she notes that her views on equality and interest in helping lift others up started when she was just a child.

"I remember being in school and reading those lofty words in our founding documents extolling equality," she said. "But looking at my circumstances, it didn't seem to apply. As a child, I could not reconcile the language of equality on the books, with the lived experiences of my parents and siblings. So, I grew up wanting to do everything I could to attain that."

Even her childhood ideas about her career path seemed to echo this sentiment of helping others. As a young girl, long before any aspirations of being an attorney or judge came into play, she would gather her dolls and those of her sisters and line them all up, where she would then "teach" those assembled "students" by reading to them from encyclopedias. This idea of being a teacher stuck with her as she got older, and though her mother eventually persuaded her to go to college and reconsider being a full-time teacher, Donald has maintained a presence in the classroom throughout her judicial career, serving as an adjunct professor at various institutions over the years, including the University of Memphis School of Law.

On a national teaching level, Donald served as president of the National Association of Women Judges in the early 90's, where she developed a curriculum to teach women how to position themselves for election in states or how to develop as lawyers to be qualified candidates for appointment to judgeships.

She even notes that after her time on the bench is done, teaching is something she would love to take on full-time.

"I've always had this desire to teach," she notes. "The exchange with people from all backgrounds is just so important. Our lived experiences and our understanding of others' experiences really play a critical role in what kind of community, and nation, we become."

"I can walk into a classroom and be beyond exhausted, but when I come out, I feel like I could float," she expounded. "It's just the ideas that invigorate me. I feel like the students today motivate me and we all teach each other."

But, like everyone else, Donald's life and career have been affected by the recent COVID-19 pandemic. From her externs operating remotely, to court appearances and oral arguments happening via Zoom, to the future definition of accepted electronic signatures, she has seen an incredible amount of change in the last few months as a result of the COVID-19 measures put in place.

"I believe a lot of the changes brought about by the recent COVID-19 pandemic can be a benefit to access to justice," Donald noted. "It is very expensive for people to participate in many aspects of the legal system. For example, prior to the pandemic, if a person had a case set for oral argument at the Sixth Circuit to argue the case in Cincinnati, people had to fund their lawyer's travel and accommodations to come and argue the case in person. Since we have been hearing oral arguments post-pandemic via Zoom, everybody can just argue from where they are, which drastically reduces the cost of participation."

As a past delegate to the ABA, she also has an extremely informed take on not only the legal profession, but also legal education itself. She notes how important the emphasis on diversity in law school, and in the legal field itself, is to the future of the industry. With or without the changes brought about by the current pandemic, she believes diversity, mentoring, pipeline programs and increased exposure to diverse experiences are all vitally important to the future of the law, as well as to our communities.

"We as lawyers have to address our huge pipeline issue, in communities both large and small," Donald noted. "We have to have greater mentorship programs and starting not just when students are in law school, because that is too late, but starting when people are in high school or even earlier."

She points out the successful Summer Legal Internship Program (SLIP) that the University of

Memphis and the Memphis Bar Association have partnered on as just the sort of program

that the ABA encourages. For the past 10 years, SLIP has sought to develop and nurture

an interest in the legal profession among young people from underrepresented groups

throughout the city. These students are placed in law firms, corporate legal departments,

or government agencies throughout the Mid-South and are required to work a total of

60 hours during the four-week program.

She points out the successful Summer Legal Internship Program (SLIP) that the University of

Memphis and the Memphis Bar Association have partnered on as just the sort of program

that the ABA encourages. For the past 10 years, SLIP has sought to develop and nurture

an interest in the legal profession among young people from underrepresented groups

throughout the city. These students are placed in law firms, corporate legal departments,

or government agencies throughout the Mid-South and are required to work a total of

60 hours during the four-week program.

"We have to let these young, underrepresented people know to start thinking about the legal profession early," said Donald. "To start exposing them to these experiences, and to really get them thinking about the possibilities, is a great thing."

She quotes her aunt on the topic of why teaching and mentoring others once you have success is vitally important.

"My aunt used to say, 'You can't live any better than you know, but when you know better, you're supposed to do better.'"

The importance of today's attorneys advocating for policy changes that positively affect change at the community and neighborhood levels is something that Donald strongly believes in. She noted that we need to see more and more of this sort of thing in order to change the way young students see the legal profession. And in the long term, it will help the legal profession become more diverse.

"We now know that the experiences that young children have with reading and exposure to positive role models and influences can have a great effect on where people set their sights," said Donald. "And for attorneys and legislators who have influence over policy choices that deal with children's health, nutrition and schools, it's these sorts of people that can really help create an environment very early on that can allow a child to enlarge their universe of opportunities.

An important detail to the future of diversity, according to Donald, is the duty of current attorneys to say that no part of the profession is off-limits to diverse students. "We have to encourage diverse students to pursue careers in prosecution as well as defense, in intellectual property as well as employment law," she said. "We have to talk to people about not only being judges, but also opening their own law firms. Many of these young people are from communities where they have no interaction with lawyers, or if they do it's because of a crisis. They need to see what is possible and expose them to the legal community early and related experiences."

It's clear from speaking with her that the future of the legal profession and legal education is tied to both fields embracing diversity, no matter what the current pandemic may bring in terms of changes.

One thing is for certain though, Judge Donald will be at the forefront of whatever the future brings, likely as the first one to embrace the change.