Department of English

English Department Newsletter

Spring 2026 | Volume 4 | Issue 2

Click here to view a PDF version of the Spring 2026 newsletter

Welcome Back!

Welcome back to all of our faculty and staff! There are a lot of exciting events happening this spring, so first and foremost make sure you're following us on Facebook and Instagram (@uofmenglish) to stay up to date.

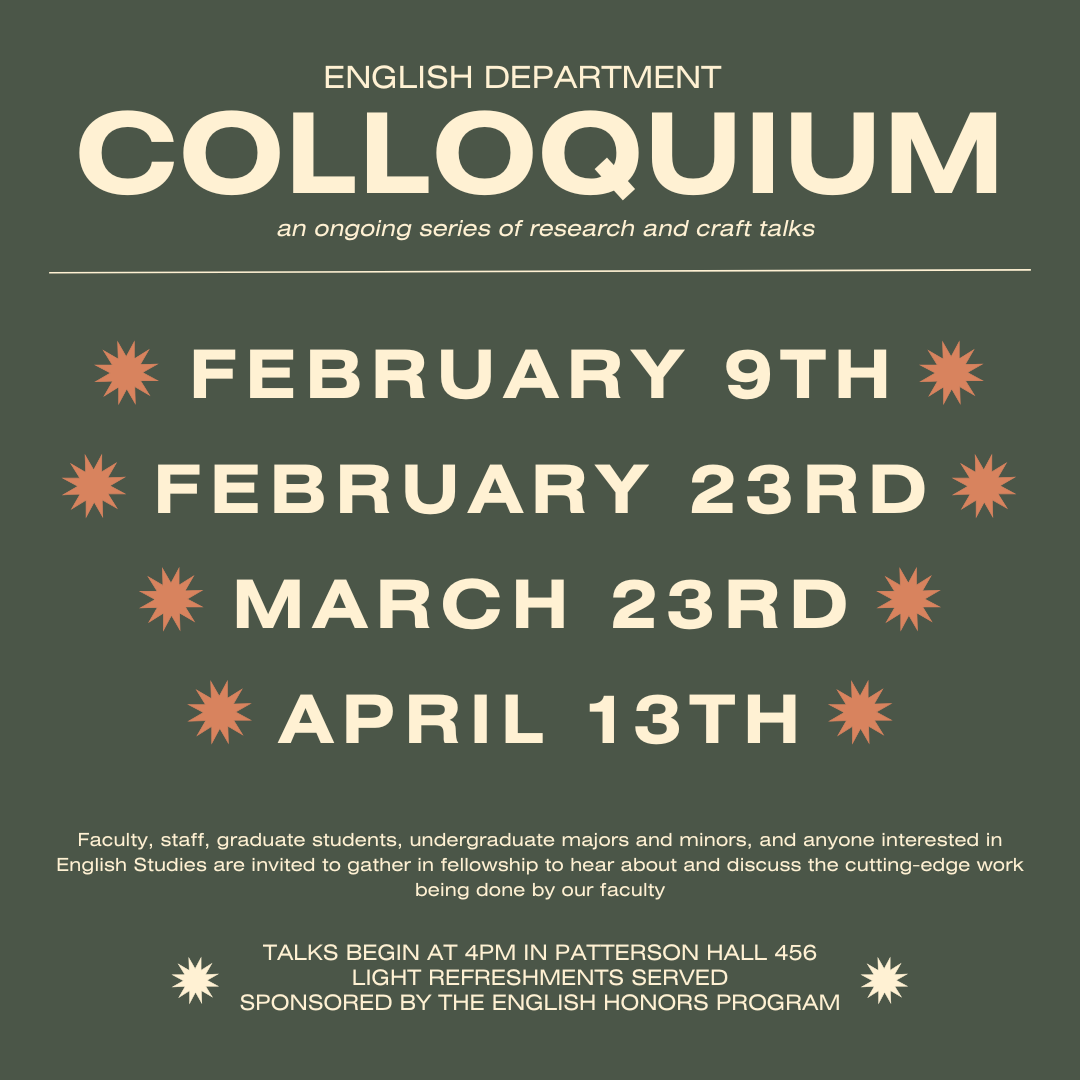

This semester, we'll welcome speakers and authors to our campus - just to name a few, The Pinch Presents will host francine harris for a poetry reading and craft interview in April, Elliott Casal will host the annual Talbot Roundtable titled “Multiliteracies, Multimodalities, and Genre” on April 23rd with a conference that weekend, and the English Honors Colloquium series returns on February 9th, this semester featuring Verner Mitchell, Emily Thrush, Scott Sundvall, and Eric Schlich.

In this issue, you’ll find additional details about these upcoming events, photos from a few of our Fall 2025 events, shout-outs to our award-winning faculty, and a publication spotlight on Dr. J. Elliott Casal’s new book!

This year we're hoping for even more involvement with the marketing and promotion of all of our amazing programs, courses, and events here in the English department. As always, if you have project suggestions or inquiries, don't hesitate to get in touch with Dr. Tucker or Dr. Gillo.

Fall 2025 Recap

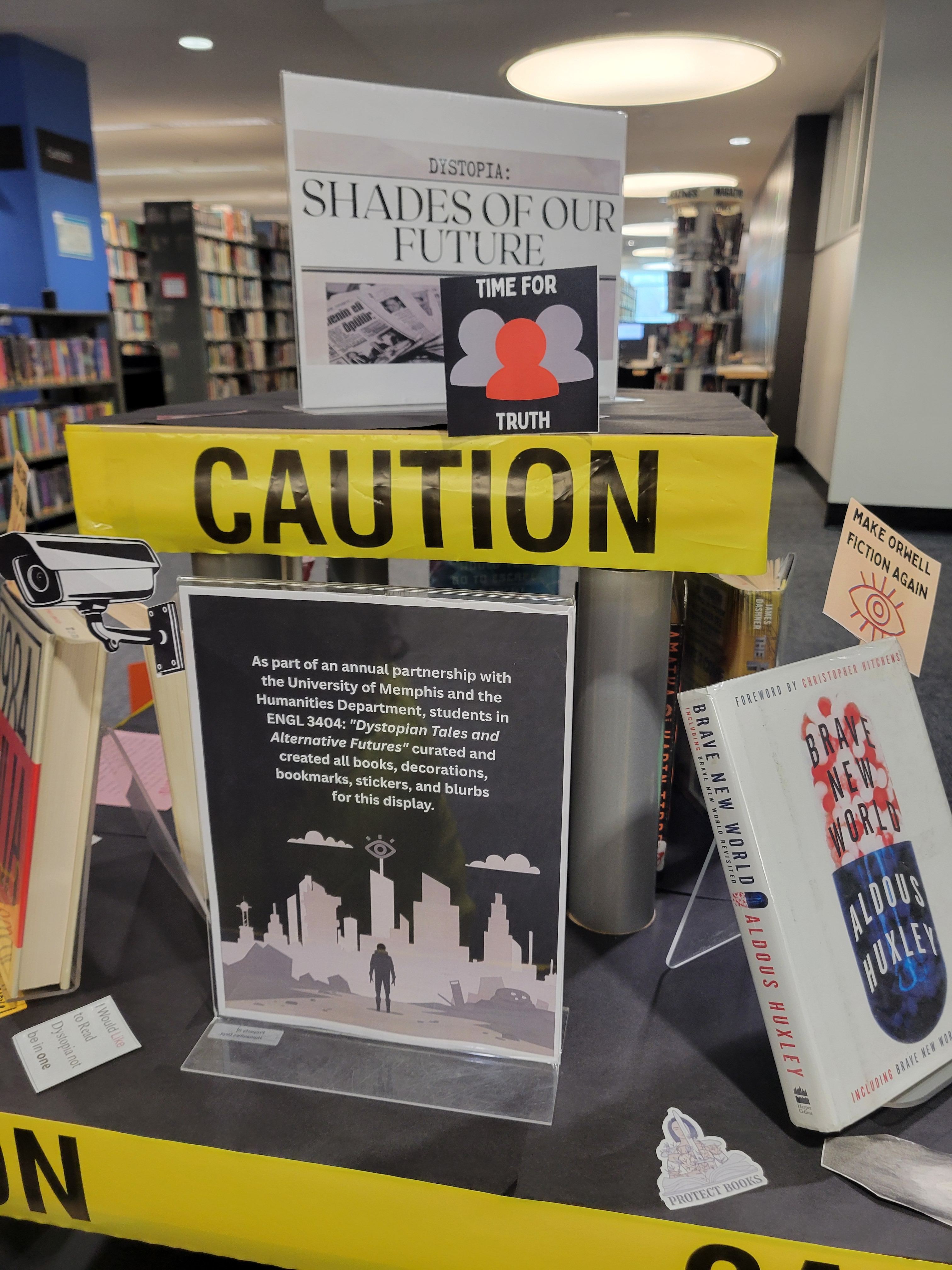

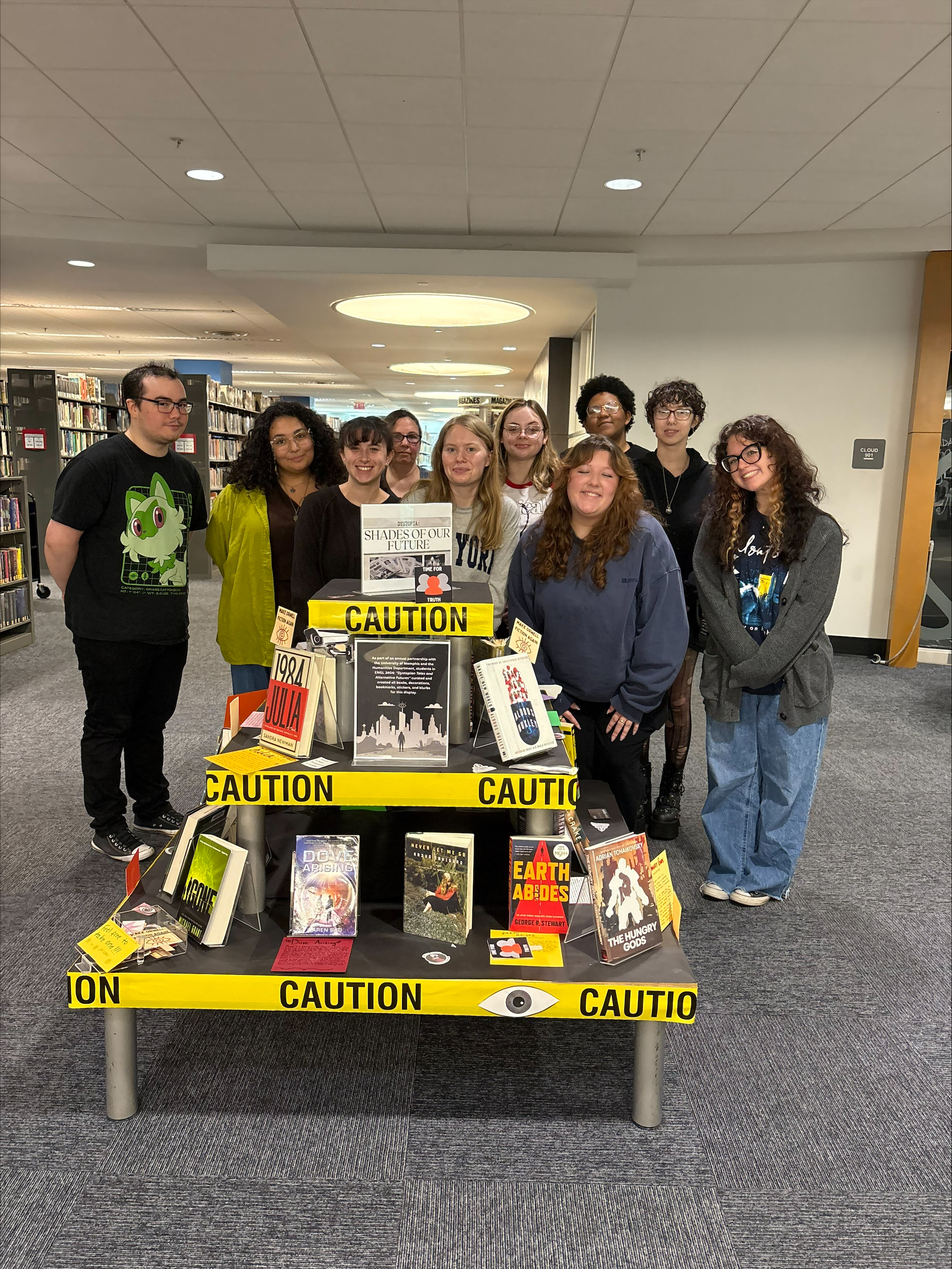

Dr. Mickalites’s ENGL 3404 “Dystopian Display” at Memphis Public Libraries

Dr. Mickalites’s ENGL 3404 “Dystopian Display” at Memphis Public Libraries

Dr. Mickalites’s ENGL 3404 “Dystopian Display” at Memphis Public Libraries

Dr. Mickalites’s ENGL 3404 “Dystopian Display” at Memphis Public Libraries

Discover Your Major Day 2025

Discover Your Major Day 2025

Save the Date for Spring 2026

English Honors Colloquium | 2/9, 2/23, 3/23, 4/13 | 4:00pm | Patterson Hall 456

English Honors Colloquium | 2/9, 2/23, 3/23, 4/13 | 4:00pm | Patterson Hall 456

The Pinch Presents | francine harris | reading: April 16th | craft interview: April 17th

The Pinch Presents | francine harris | reading: April 16th | craft interview: April 17th

Deb Talbot Roundtable & Conference: Multiliteracies, Multimodalities, and Genre

Deb Talbot Roundtable & Conference: Multiliteracies, Multimodalities, and Genre

April 23rd | Location TBD

*conference to follow that weekend*

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram account to stay up-to-date on all the English Department happenings!

Faculty Publication Spotlight

Dr. J. Elliott Casal, Concept-Based Language Instruction and Genre-Based Second Language Writing Pedagogy: Provoking and Assessing Development

Genre-Based approaches to Second Language Writing Instruction have become a powerful

and popular means of assisting second and multilingual writers in learning to engage

in professional, pedagogical and academic genres that are often high-stakes. This

book presents a framework for teaching second language and multilingual writing that

integrates Concept-Based Language Instruction and Genre-Based Writing Pedagogy. The

authors present three large-scale implementations, within a graduate legal writing

context, a cross-disciplinary doctoral research writing context and a graduate mechanical

engineering context, and demonstrate how the pedagogical and theoretical framework

is interdisciplinary, flexible and comprehensive. It provides a means of theorizing,

researching, teaching and assessing the development of second language writer genre

knowledge from nascency through expertise and equips second language writing instructors

with a theoretical and practical toolkit to empower student writers to be more agentive,

aware and strategic in their writing.

Genre-Based approaches to Second Language Writing Instruction have become a powerful

and popular means of assisting second and multilingual writers in learning to engage

in professional, pedagogical and academic genres that are often high-stakes. This

book presents a framework for teaching second language and multilingual writing that

integrates Concept-Based Language Instruction and Genre-Based Writing Pedagogy. The

authors present three large-scale implementations, within a graduate legal writing

context, a cross-disciplinary doctoral research writing context and a graduate mechanical

engineering context, and demonstrate how the pedagogical and theoretical framework

is interdisciplinary, flexible and comprehensive. It provides a means of theorizing,

researching, teaching and assessing the development of second language writer genre

knowledge from nascency through expertise and equips second language writing instructors

with a theoretical and practical toolkit to empower student writers to be more agentive,

aware and strategic in their writing.

Read more and order here!

Check out this blog post about the book here.

Click here to see more creative works by our faculty

Faculty Recognition

Dr. Kathy Lou Schultz

Dr. Kathy Lou Schultz was selected as an Artist-in Residence by the Kimmel Harding

Nelson Center for the Arts (KHN). KHN is a small residency that hosts only 5 artists

at a time, including painters, composers, videographers, poets, multidisciplinary

artists, non-fiction writers, and novelists. Her creative work has also been supported

by Ragdale and the Centrum Foundation.

Drs. J. Elliott Casal and Katherine Fredlund

Grant Award: $3,999,998

2026-2029. Teaching and Learning with AI: Transforming Postsecondary Education with Scenario-Based

Tasks. US Department of Education.

Click here to view a PDF version of the Spring 2026 newsletter

English Department Newsletter Archive